Last week, the FT ran a series of articles on public spending cuts. Its summary:

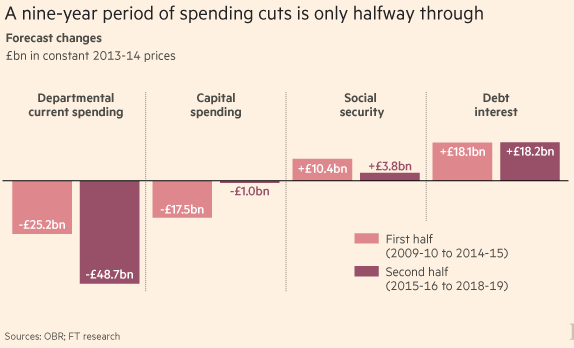

Half way through 9 years of planned austerity, the FT has uncovered that more than half of government cuts are still to come. And they will be twice as large as David Cameron’s £25bn figure.

I had a busy week so still haven’t finished reading all of it. If you have time, it’s well worth working through.

The FT’s main finding, after crunching the numbers on the government’s forecasts, is that a further £48bn of spending cuts will be needed in the next parliament if an absolute surplus is to be achieved by 2019. This is £10bn higher than the figures calculated by the IFS and the Resolution Foundation (see previous post). There are (as I read it) two reasons for this. Firstly, it includes the cuts for 2015-16. These budgets will already have been set by the time of the next general election though most of the year they apply to will fall into the next parliament.

Secondly, the FT has also included “the effect on departmental spending of rising numbers of pensioners and increases in pension payments” in its analysis. Look at the ‘Social security’ column; the FT reckons spending will continue to rise, while the government’s forecasts show it falling, albeit very slowly, over the next four years. (Given what the IFS said yesterday about pensioner benefits, housing benefit and tax credits combining to thwart the government’s attempts to cut welfare costs, the FT’s take may well turn out to be right.) To meet the deficit reduction target, any increase in social security spending has to be found from cuts to public services.

According to these calculations, then, the austerity programme is only half-way through and, in terms of cuts to spending on day-to-day public services, not even that.

As Chris Giles says:

So far, the public sector has coped better than many expected. But with employees more restless about slow wage growth and the easier cuts already achieved, many experts think taxes are more likely to rise than fall after the next election to protect public services and keep the deficit falling.

A week or so before the FT articles, Deloitte published its State of the State report. Its tone is broadly in support of the government’s deficit reduction plans, which makes some of its caveats all the more interesting.

The fiscal consolidation programme can be viewed in two distinct halves, divided by the 2015 General Election. The spending cuts in each half will drive different cost reduction activities in the public sector. The first half has seen cuts to public services and administration that were typically managed through pay freezes, contract renegotiations, savings realised through shared service arrangements and workforce reductions. At least 95 per cent of English councils, for example, are now involved in some form of shared service arrangements.

The second half of the programme will be substantially more challenging. As the cuts reduce budgets, public sector organisations will not be able to cope in the same ways. Those faced with particularly deep budget reductions will need to rethink how they operate, the services they provide and the outcomes they can deliver. In local government for example, councils are likely to focus on services targeted towards people in particular need and move away from the services they are not legally required to provide such as leisure facilities.

While the first half of the consolidation period has seen public sector organisations cut costs and deliver tactical improvements, the second half will see many redefine themselves and move to lower-cost models in order to cope with the next wave of budget reductions.

In other words, all the obvious savings have been made, a point not lost on the public sector managers interviewed for the report.

While the executives we interviewed were generally upbeat about their change management and resilience over the past five years, most were less optimistic about the next five. Some told us about a sense of fatigue and many expressed a real worry that their organisation or its wider sector would not be able to cope with continued austerity beyond the next UK General Election.

Most recognised that the cuts to come would be more challenging than those already achieved. They told us that the ‘low hanging fruit’ has been exhausted and that their approaches to cost reduction in the past five years will not be sufficient for the next five. The changes they expect to make to cope with further funding reductions will have increasingly profound implications for their organisations and the services they deliver.

Public sector organisations have frozen pay, cut back office functions, merged departments, shared services with others organisations, removed layers of management and re-worked their processes. They have also hammered their suppliers, sacked their contractors, slashed their training budgets, eaten into reserves and quietly cut services they think people won’t notice, at least, for a while. Some of this has led to real efficiency savings, maintaining services while reducing their costs. In other cases, organisations have simply taken out costs which will damage services in the longer term or which will appear somewhere else.

In addition to budget cuts, many interviewees spoke about increased demand for their services created by cuts in other areas of the public sector including welfare reform.

This is a particular problem in areas like social work, housing and, of course, A&E. If the charities that used to look after the distressed, the alcoholic and the drug-damaged have their grants withdrawn, the people they used to help will eventually turn up at the local hospital or council offices. All of which puts extra pressure on services.

Then there’s this:

Public sector chief executives believe that national politicians could do more to lead a national debate in what citizens should expect from the public services and local politicians could do more to engage citizens in what they should expect locally. At present, there is a perception that both national and local politicians often criticise public services but rarely help citizens appreciate that spending reductions may lead to reduced levels of service.

The result is that citizens may have unrealistic expectations about state provision at a time when citizens are expected to take more responsibility for themselves.

To sum up, then, making a further £48bn of spending cuts means that the state will have to stop doing some things. The Deloitte report mentions leisure facilities but flogging off or closing parks and sports centres won’t get us anywhere near the savings needed. Those charged with making the cuts know that this means a rapid descoping of public services.

No-one has explained this to the voters though. Citizens have unrealistic expectations because politicians have allowed them to think that the axe will fall on someone else. Depending on party ideology, those bearing the brunt of the cuts will be lazy welfare claimants, migrant benefit tourists, underworked public servants, over-bonused bankers or the rich. No-one is telling Mr and Mrs Middle-Income that they are going to have to pay more tax and/or see much more drastic public spending cuts.

The FT editorial which accompanied its Britain and the Cuts report was scathing:

[T]his is not the impression anyone would receive from listening to recent political rhetoric. In a recent conference speech, David Cameron, the prime minister, misleadingly claimed that the government was four-fifths of the way to its goal of achieving fiscal balance, leaving scope for a costly middle class tax cut. Financial Times analysis, alongside that of think-tanks such as the Institute for Fiscal Studies, suggests instead that Britain is less than half way towards Mr Cameron’s fiscal surplus.

It had sharp words for Labour too:

The prime minister is able to get away with this obfuscation because of disarray in the opposition Labour party. Asked to explain how he would deal with the budget squeeze, Ed Balls, the shadow chancellor, offered up savings of just £100m on child benefit – barely a thousandth of what is needed. UK voters face the prospect of an election where the overriding political issue is either ducked or fudged.

It’s more than just Labour disarray though. The party is colluding in the fiscal muddying. This weekend it was shouting about taxing millionaires and bankers’ bonuses. However you decide to define banks, bankers and bonuses, none of this will raise very much money. Labour’s Mansion Tax is simply Land Value Tax Lite, a property tax but only for those with very big houses. A tiny number of people would pay it and it would make very little difference to the property market or to tax revenues. Labour’s message is just the flip side of the government’s. Don’t worry, someone else will pay.

The FT concludes:

Fiscal credibility should mean setting out plans that are realistic and believable. None of the major parties has come close to setting out an answer to Britain’s fiscal dilemma. At the very least, they should come clean with voters about the nature of the questions that need answering.

If they don’t, then a lot of people will be in for some surprises over the next five years.

Ah, did we forget to mention the 8p rise in income tax?

Of course we’ll eliminate the deficit by the end of the decade. It will be gone by 2030!

Well I know abolishing social services wasn’t in our manifesto but….

After the election, whoever has won will have to move out of La La Land and make some hard choices about what happens next. At least one of the three pillars in the 2015 dilemma will have to give. My bet is that all of them will; higher taxes, more borrowing and some spending cuts. Yet here we are, 6 months before a general election, with politicians still trying to kid us that someone else will pick up the tab.

Reblogged this on sdbast.

Hum how come we owe monies to the banksters when the public bailed them out banks going bust wouldn’t have hurt the ninty nine percent who aint rich that the tories have since thatchers days sold us out in monies savings and jobs are we ghe ninety nine percent going to pay fo the one percent yet again wouldn’t it be better putting right the wrongs firstly bringing back our jobs to government and all the utilities then wonder why we let this lot sell us down the river yet again we the ninty nine percent dont owe them they owe us I realy wonder were after all thachers sell off nobodys stating it was a sell out of the British public by greedie people

Would love to see an election “debate” (with all parties) based on these figures.

Put all “leaders” in front of a programme (like the one FT has) and asked them to apply their parties choices. No PR/BS, just a programm and please all together apply cuts/taxes as you want to.

That would be nice to see. In the end, we can compare what each would do…

Btw, what is you estimate of the revenues from a proper LVT?

Reblogged this on Views From The Boatshed and commented:

Sobering article from Flip Chart Fairy Tales about the true size of the cuts (or tax increases) required to get rid of the fiscal deficit. The government claims we’re about four fiths of the way through the austerity process; everyone else who has crunched the numbers says we’re only about half way through. The article is based on work done by the Financial Times which concludes in a recent editorial:

“Fiscal credibility should mean setting out plans that are realistic and believable. None of the major parties has come close to setting out an answer to Britain’s fiscal dilemma. At the very least, they should come clean with voters about the nature of the questions that need answering.”

And meanwhile we refuse to use the money helicopter, with inflation forecasts to be below target for years.

Two comments:

-What is the real inflation and specifically one experienced by low incomes? Just think of where the prices are heading for transport costs, housing and food/energy the last 5 years. So the below target is not really below target (even RPI is at 2.4%!). In 2011 supposed essential inflation was near 8% …

-Agree about helicopter money. But they are already have done this but only (yes only) for the asset holders (QE) . Sadly the gov/BoE continue introducing policies that only support asset-holders (QE/FLS/HTB) etc.. It would be nice if helicopter money was applied to all of the economy instead… Tenants/Youth/Savers and pensioners, instead of asset holders…

Would there be any sense of what could be raised by a yearly tax on second, third, fourth etc properties in the UK, whether empty or rented, holiday let, or permanent tenant? In addition, a one time tax based on HPI* over the past 10-15 years on any second, third, fourth etc properties located in the UK.

*Scale of tax being offset against measurable improvements to the property that have resulted in value increase.

Are we talking billions do you think?

These posts are the worst kind; convincing and thoroughly depressing. I am certainly bracing myself for some fairly substantial tax rises over the next parliament or two.

In my darkest “somebody else will pay (as well)” moments, I wonder how much would be raised by abolishing employee’s NI contributions and raising the basic rate of income tax to 32%, to be chargeable on all income, including savings and pensions. I can justify this to myself in a few ways:

15k annual ISA allowance ought to give ordinary folk ample scope to avoid it on unearned income;

If you believe the fallacy of NI being an insurance then you have to regard a great deal of it to be health insurance; private health insurance premiums are still charged to pensioners, so it is reasonable that the public health insurance should be too.

Obviously, this would be a temporary measure to be repealed on the day I retire.

I wonder how much it would raise?

Western democracy is based on promising the majority that someone else will pick up the tab, and that their choices have no consequences . Do that continually since 1948 and you eventually get to this point.

The next few years are going to be fascinating.

One of your best blogs ever retweeted with comment. This is basically a list of excuses Labour will use not to save the NHS. I hope I’m wrong.

Pingback: Avoiding Fiscal Fudge | Homines Economici

Pingback: I lied - OverThePeak.com

Not a particularly surprising blog Rik but timely and nicely written . I have no understanding as to why others find it so surprising . Gordon’s spendthift years were always going to have a payoff sometime . He inherited an economy that was very approximately in balance and with my tacit approval blew billions we didn’t have with little perceptible result . It mostly went , as usual , in new management posts and salaries ..Doh ! My local ‘services’ saw little reall investment . The usual Labour Party legacy , will I never learn !

Once again PHearn , I think you’re quite correct , although to describe democracy thus is over egging it a tad but , the point is well made for here . Their (many of the respondents here) problem is that having been brought up with credit the children who respond here so angrily don’t seem to understand that it all has to be paid for somehow , sometime by somebody which will undoubtedly be , them and nobody else .

Get used to it , our benefits ; education , pensions and the “free” health service hasn’t been replicated anywhere else in a similar situatiaction , with good reason . It was the most wonderful concept in its time and perfectly affordable , but now ? Maybe if our private sector had really been world class and earned reall wealth , just maybe , but right now there’s little money in metal bashing and for some reason we seem to be ahead of the game in financial services so despite my natural antipathy let’s stop the childish sniping and agree that for the moment they’re just about our best hope .

As you rightly say , the next few years will be interesting indeed . As for “helicopter money” , saints preserve us , another slick title to put off tomorrow’s payback .

Awful init ? But still so much more comfortable and envied by most of the rest of this planet .

“the children who respond here so angrily don’t seem to understand that it all has to be paid for somehow , sometime by somebody which will undoubtedly be , them and nobody else”

Some of us “children” certainly do understand that. Perhaps that is why we are a little miffed about it.

“Our benefits ; education , pensions and the “free” health service hasn’t been replicated anywhere else in a similar situation, with good reason . It was the most wonderful concept in its time and perfectly affordable, but now?”

One of the things that made it so affordable back when it started was surely because it didn’t need to pay for that much. Most people died soon after retirement and it isn’t too much of an exaggeration to say that healthcare was closer to occasional brow-mopping as you waited to expire than the expensive, often pre-emptive, technological marvel it is today.

Unfortunately, over the last this system has been too successful to allow us to continue to afford it. The better healthcare and education that my parents’ generation enjoyed over their own parents generation leaves a majority of them embarking on a long retirement, expensively supported by the NHS.

In many ways I find it difficult to begrudge them this. As you say David, the system was wonderful and my parents’ generation has planned to live with it and not without it in their dotage. But successive governments and electorates have failed to acknowledge until recently that we are getting out of our depth. I’ve seen stats on this blog suggesting that we are already spending 10% of GDP on state pensions, which only gives individuals a fairly paltry allowance. This number, along with the NHS bill, will only grow.

I don’t really want to see the end of all this, particularly (substantially) free at the point of care healthcare, though I am open minded about how it could be provided. It is clear that more taxes will need to be collected to pay for it. It means I’ll have a higher tax-bill. I’ll live and I’ll belly-ache but on balance it’s better than the alternative.

What would be nice though, would be if the protected class of today’s and near-future pensioners, who despite low interest rates have done better out of the last few years than other population cohorts, would accept some higher taxes too, perhaps by reducing or eliminating their income tax discount which comes from not having to pay National “Insurance”; share the pain, a little.

If we can’t raise some more money to pay for it (and I would doubt that it can come only from GDP growth, even on the most optimistic of projections), there is a real danger that the “cradle to the grave” promise will be all to literal. State pensions and much more worryingly, a free healthcare system, could be buried with those that were born around the time of the NHS’s inception.