Four months ago, there was much cheering and dancing on George Osborne’s political grave (or at least his political cold-storage) as he announced the government’s abandonment of his deficit target and his own resignation.

Some people, including the leader of the opposition and the shadow chancellor, claimed that this was a U-turn.

I welcome Osborne’s decision to listen to the calls made by myself & @jeremycorbyn to drop his failed surplus target pic.twitter.com/vv4gd0aLuq

— John McDonnell MP (@johnmcdonnellMP) July 1, 2016

Today Osborne has bowed to Labour pressure by scrapping his failed spending target https://t.co/Y1PsN63vya

— Jeremy Corbyn MP (@jeremycorbyn) July 1, 2016

Even the Daily Mail said that the government would “abandon George Osborne’s austerity agenda.”

The line was repeated by excited people in my Twitter timeline. George has abandoned the deficit target so it’s the end of austerity. Game over!

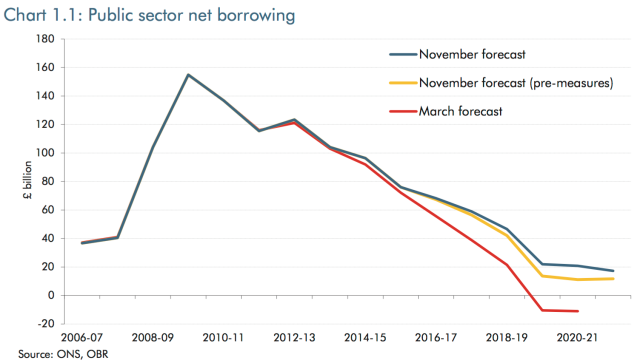

If anyone still believed that, the Autumn Statement should have put them right. The OBR’s fiscal outlook report shows that, when it comes to public service spending, very little has changed. The forecast looks pretty much as it did in March of this year, only with the fall in per capita day-to-day public service spending now continuing into the next decade.

With NHS, schools and defence budgets protected, to an extent, this means an ever tighter squeeze on everything else. The cost of the Brexit process, including thousands of extra civil servants, will also have to be found from this shrinking pot.

No, the reason for the abandonment of the government’s target is not an end to austerity it’s simply that, even with continuing public service and welfare cuts, the public finances are now in such a dire state that eliminating the deficit by the end of the decade is now all but impossible. Lower economic growth means lower tax receipts. Even without the modest increases in capital spending, weaker growth meant that the government was already on course to miss its target.

Chart by Ben Chu based on OBR figures.

This forecast assumes that the government is able to achieve all its proposed cuts to public spending and social security. This is unlikely to be any easier than it looked this time last year so even the new deficit target might prove to be a tall order.

In any case, the Brexit vote has made economic forecasting even more difficult than usual. It has turbocharged Robert Chote’s donkey. The OBR has based its projections on the UK leaving the EU in April 2019, in line with the prime minister’s statement but even then, there are so many possible variations on the terms of exit, it is very hard to predict what the economic impact might be.

What we can be reasonably sure of, though, is that Brexit will not improve the economy in the short run, which means that cuts to public service spending will continue for the rest of the decade. Much about the next few years is uncertain but, whatever else happens, austerity will be with us for some time yet.

Reblogged this on sdbast.

The UK economy is the Kobayashi Maru scenario and Phil Hammond is Captain Kirk.

No. Unless there is some solution no one has found to the dismal economic state of the UK.

It’s like the whole world has forgotten how we got out of the Great Depression, with some help from those chaps called Keynes and FDR.

This obsession with the budget is causing us to slowly sink into secular stagnation. The way out is to deficit spend our way to full employment, the budget will take care of itself. Hopefully it won’t take a world war this time around, but of course war time is when everyone drops their objections to deficit spending.

It was not Keynes or FDR who ended austerity so much as the onset of World War Two and the requirement to press all societal assets into action in order to wage total war.

The last person to attempt Keynesian-style reflation was then French Socialist President Mitterrand in 1985. The result was disastrous, as the borrowed money pumped into the system leaked out of the French economy as French consumers bought German cars and Italian shoes, while those running French businesses simply upped their prices and took suitcases filled with cash across the border to deposit in Swiss banks, while leaving higher amounts of borrowed funds not being able to be paid out of non-existent central government tax revenues. This was the final bout of stagflation following after the 1970s.

That was when neo-Keynesianism finally died and neo-liberalism finally triumphed.

Keynesian-style reflation only works within a sealed economy, not an open one.

This is one of the reasons why the EU can have such a baleful influence on national economies, as most obviously seen in the case of the Greek economy.

One possible Brexit benefit may be that Britain will be able to exercise greater control over its own economy after Britain finally leaves the EU. Then – maybe – a more sealed economy may make Keynesian-style reflation a possibility in future.

I’m not sure what your current view is Rick. Over the last couple of years you have comprehensively demonstrated that the UK economy is slowly going nowhere. Now the British people have voted for change you say we should have kept to our original plans.

The OBR forecasts follow from their assumptions, but changing the path of the economy by challenging the basis on which it operates is what the point of leaving the EU was. The OBR says there is increased uncertainty. Yes, that was the point of voting to leave, to give us the opportunity of breaking out of this straightjacket. More freedom inevitably means more uncertainty.

The EU had a clear path for us. For the south-east a hub of pan-European commerce with professionals from all over Europe engaging in high-value work. For the rest of the UK low-wage jobs staffed by workers from the rest of the EU whilst the local populace are shut out (as observed by one of the MPs on a recent visit to a Sports Direct warehouse). The growth prospect for UK residents was poor as there was no reason to provide training or career development for native staff when European imports were cheaper. We were tied to a low-growth protections zone, and faced protectionism within that from countries such as Germany that have ridden roughshod over the free market in services – one of the four pillars of the EU.

The survey says that the prospects for low-paid workers are poor, but perhaps some of those low-paid workers may manage to raise themselves out of their current social caste, something not possible if we remained in the EU. Lord Kerr exposed the thinking behind the establishment on the EU when he said recently we needed immigration because the “native Brits are so bloody stupid”.

Chart 1.1 above shows that Public sector net borrowing rose dramatically in the run up to the 2008 financial crash and that the level of borrowing has only gradually decreased since then.

I am guessing that the money borrowed was used for quantitative easing – is that right?

If it is, then surely central government must be holding onto assets of some value to pay back what they have borrowed?

The only other alternative is that they have given our money away to others for nothing.

Does anyone have any idea as to what central governments have been doing with our money?

That is in addition to allowing real inflation to reduce their own debts to the rest of us?