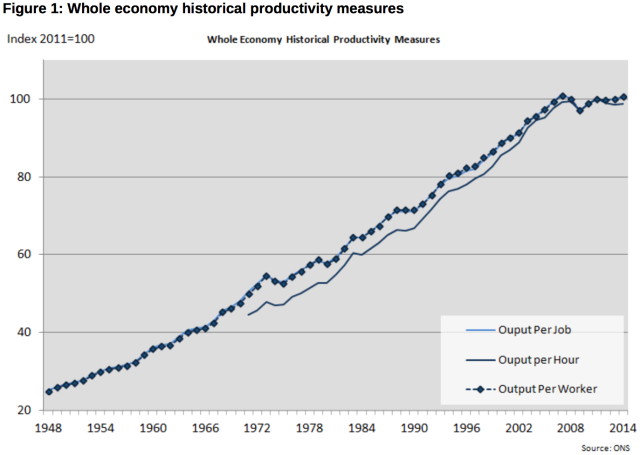

“The absence of productivity growth in the seven years since 2007 is unprecedented in the post-war period,” said the ONS after its figures showed yet another fall in productivity.

Whichever way you measure it, it’s rubbish.

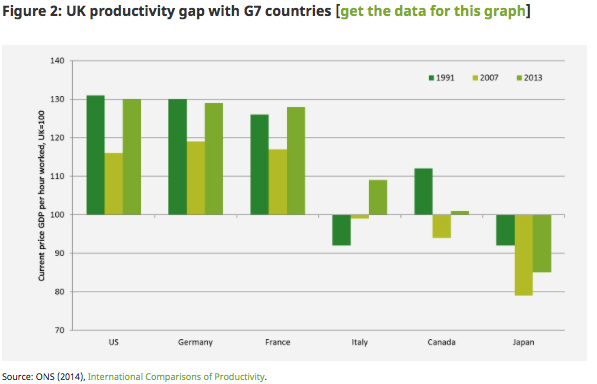

It’s not only rubbish when compared to past performance, it’s pretty bad when compared to most of the other G7 economies. We closed the gap during the 1990s and 2000s only to see it open up again after the recession.

Chart via IFS

LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance published a pre-election briefing on productivity a couple of weeks ago. Among its conclusions:

UK GDP per hour is currently around 17% below the G7 average. This is due to low investment especially in infrastructure and innovation, poor management and weak intermediate skills.

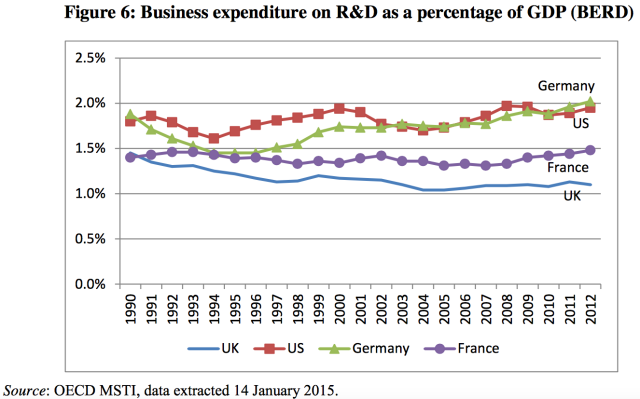

This chart, taken from the CEP report, shows that, while R&D investment has risen in Germany, France and the US, it has been falling steadily in the UK over the past couple of decades.

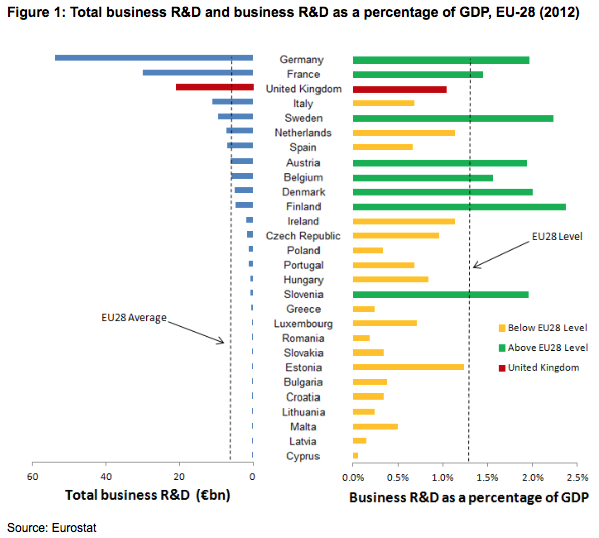

Relative to the size of its economy,the UK’s R&D spending is now well below the EU average.

Chart via ONS

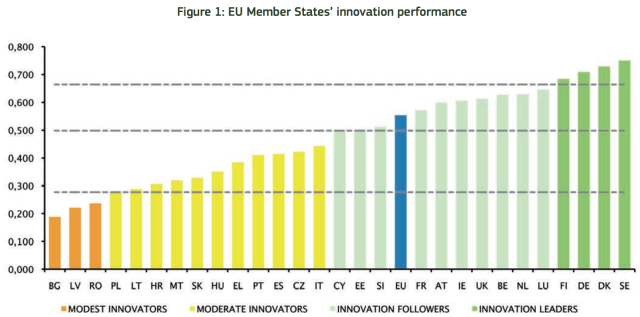

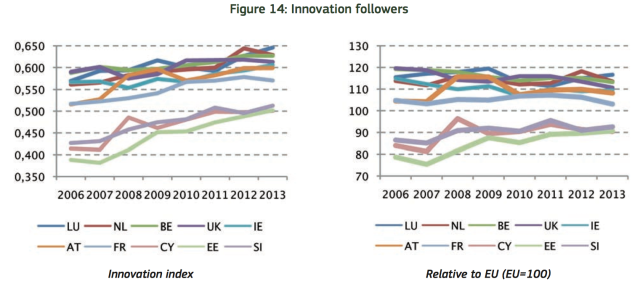

We British like to think of ourselves as a creative nation but according to Eurostat’s innovation index, which measures innovation in a number of areas, the UK is now a follower not a leader.

Not only that but its performance has lagged behind when compared to others in the follower group.

Growth performance of Ireland (1.0%), Belgium (0.9%) and the UK (0.5%) is well below that of the EU and their relative performance has worsened over time.

In other words, mid-table in the second division, in danger of sliding towards the relegation zone.

Does this mean that our scientists are unproductive too? Far from it. A BIS report in 2013 found that the UK research performs extremely well when compared with other countries.

While the UK represents 0.9% of global population, 3.2% of R&D expenditure, and 4.1% of researchers, it accounts for 9.5% of downloads, 11.6% of citations and 15.9% of the world’s most highly-cited articles (see Figure 1.1A).

In other words, despite being a small country that doesn’t spend much on R&D, the UK produces world-class research. As the report says:

The UK is a highly productive research nation.

The trouble is, not much of it finds its way into the development of things which might boost the rest of the country’s productivity. As Helen Miller of the IFS remarked:

There is also a weakness in the extent to which science is commercialised and translated into new products and services.

As Ethan Mollick said, innovation requires both innovators and suits. Good managers are crucial to innovative and knowledge intensive industries. Without a supporting business infrastructure, there is nowhere for good ideas to go.

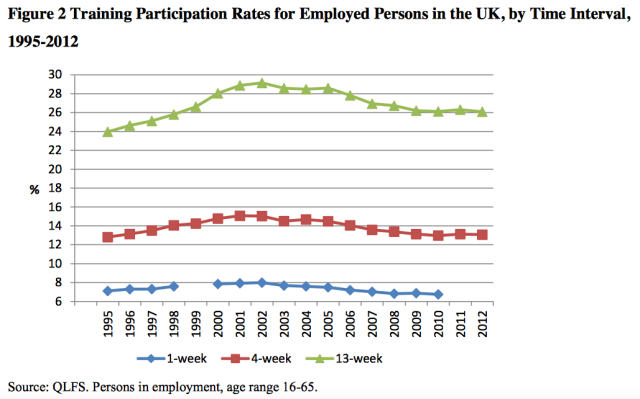

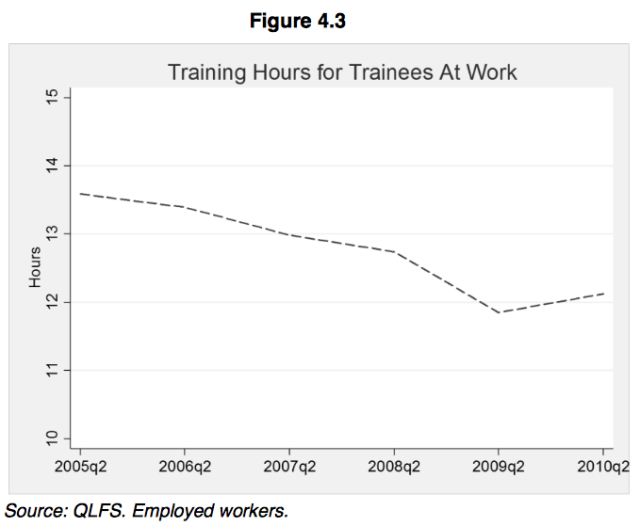

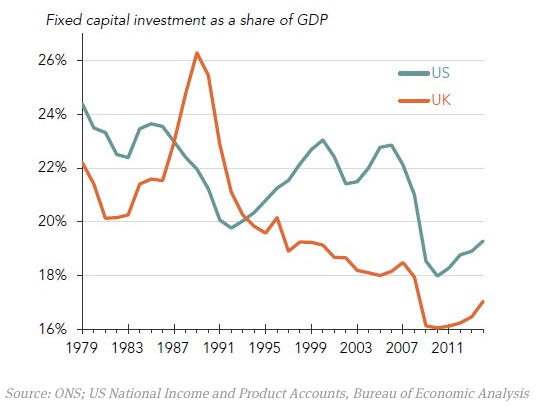

Of course, R&D and innovation aren’t the only factor affecting productivity growth but when you look at it alongside the fall in training provision and general business investment you start to see a pattern.

Organisations have been doing less of the sort of things that improve productivity and this has been going on for some time.

Coincidence? Not according to Andrew Smithers. This is exactly what senior business executives have been rewarded for doing, he says:

A major cause of the decline in investment in recent years that has fed through more recently to falling productivity has been the change in the way senior executives are paid. The massive jump in their remuneration is largely due to the rise in incentive payments that are linked to short-term changes in profits and share prices. As such, management now has a much greater incentive than before to run companies in ways that will enhance these measures in the short term, even though the price is lower long-term investment.

Crucially, underinvestment enables companies to gain market share in the short term, as their consequent lower costs allow them to reduce their prices while maintaining the same margins and thus undercut their competitors.

In other words, if it’s bonuses based on the short-term share price you’re after, it actually pays to cut investment. If that screws the organisation in the long run, who cares, you’ll be long gone.

Because companies usually have long life spans, we might expect them to take a more considered approach. However, chief executives can rationally expect only to be in office for a few years. The change in incentives has therefore shifted the balance of decisions away from the longer-term interests of companies to the shorter-term interests of management. The result has been a sharp decline in investment, an increased drive for higher margins and a preference for adding labour rather than capital equipment in response to rising demand. These preferences naturally results in weak labour productivity.

Falling investment and its consequence, low productivity, suggests that management in the UK has become more short-termist. Given what we know about pay and reward, it’s likely that remuneration played at least some part in that. So far, there are few signs of any significant change.

Earlier this week, David Cameron described Britain as a buccaneering country. Buccaneers attacked when they saw rich pickings, grabbed as much as they could and then made a quick getaway. Maybe he’s right.

Reblogged this on sdbast.

The situation you describe has been true for – at least – the last 40 years.

In 1964, the Labour government set up a Department of Economic Affairs (DEA) under the leadership of Cabinet Minister George Brown. ‘The most important function of the DEA was to prepare a ‘National Plan’ for the economy.[10] Brown became personally identified with the project, which helped increase enthusiasm for it among officials and the Labour Party, while also interesting the press. After nearly a year’s work the Plan was unveiled on 16 September 1965, pledging to cover “all aspects of the country’s development for the next five years”. The Plan called for a 25% growth in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) from 1964 to 1970, which worked out at 3.8% annually. There were 39 specific actions listed, although many were criticised as vague.[11]. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Brown,_Baron_George-Brown.

According to Wikipedia, ‘After the 2005 general election the DTI was renamed to the Department for Productivity, Energy and Industry,[6] but the name reverted to Department of Trade and Industry less than a week later,[7] after widespread derision, including some from the Confederation of British Industry.’ Note: widespread derision – says it all.

UK approach towards productivity has always been ludicrous in my working lifetime – over 55 years – and seems to get no better. This fact indicates that Britan has the worst managers in the world to my mind. Our whole society and economy is geared – and has ;lways been geared – towards serving the narrow interests of a very narrow social elite.

Bullingdon Britain Rules – OK?

I was working on long-term technology strategy in a UK high tech company in the 1980s.

The negative impact of the “manage for shareholder value” advice, which arrived then from consultants, was immediate and tangible.

I concluded then, and still feel now, that the only innovation was going to come from companies run by an owner motivated to “do something special” (e.g.Dyson).

Any business managed by a good” professional” manager (working the way he is taught and rewarded) should be stripped of all but cash-flow-generating assets with an investment horizon no greater than the share option exercise delay. Product and service quality should be the minimum required to meet contractual needs and to avoid escalating “quality costs”.

No “professionally-managed” organization will innovate until the managerial rewards are changed.

Low productivity – due to low investment and poor management – dates back to the late nineteenth century and is largely a product of empire. Too much British capital went abroad (both to the colonies and, via the City, other extractive economies – e.g. South America) to seek high, short-term returns; while too much management talent was diverted away from domestic industry to the colonies, the City and government.

Even in the post-WW2 period, too much money (after paying US debts) was initially spent on the dwindling empire and maintaining an international role beyond our means. This led to insufficient industrial investment in the 40s and 50s and a failure to rationalise key industries (e.g. automotive). Management talent remained weak, in part because a lot of clever working-class kids were diverted into the public sector and the emerging service industries (by the 80s, a lot were being diverted once more to the City).

The spider at the centre of this web, and the lasting legacy of empire, is the City. While that remains unreformed, there is little prospect of a flowering of productivity elsewhere. NB: A chunk of the productivity “catch-up” we saw in the 90s/00s was due to “innovation” and output price inflation in the financial sector (i.e. PPI, fat fund management fees, flotation and M&A fees etc).

Not at all John . Reports like this run contrary to what I’m told by friends and aquantencies still running and employed by companies previously known by me (I am , thank god , retired after an almost equally long working life) . Most are experiencing major investments in machinery and / or staff right now ….and long my they be able to continue that .

I would add that I was much more successful at thwarting productivity when a shop steward than I ever was attempting the opposite as a company owner . The biter bit you might say .

Your comment regarding British managers though is only slightly harsh . Most I worked under had little idea , and it must be added , neither did I ! I often felt that my company did very well despite me and because we were really good at what we did .

Narrow social elite ? Not in my experiance post 70’s . Almost every company I knew was a recent start up by someone from the shop floor , and very successful most of them became . So , yes in my dim distant youth of the 60’s there were plenty of incompetent suits and family sinecures but after the well overdue reality check of the 80’s competition was too fierce for excess deadweight .

Having said all that I agree with the general thrust of this blog which was much more to do with the short term ‘ism of returns on investment . Certainly in Germany I experienced a much more long term ‘joint’ approach between industry and investors , and that’s what engenders the confidence necessary for investment in productivity .

Reblogged this on Forwardeconomics.

This is generically persuasive – I totally buy into the concept that short-termism in management damages investment. However, something special occurs in Britain, because our management structures are rarely that much more short-termist than the USA, but we have even lower investment…

Our history is clearly part of it as others have suggested.

I think there’s some kind of Oxbridge malaise at work too though.

It is literally astonishing when one realises that almost everything to do with the original Industriial Revolution came about as a result of private – often individual – research and development, as well as private – often individual – investment.

The manufactories, canals, railways, shipyards, potteries, coal mines, iron works, steel works etc. all began as privately-owned and administered enterprises. Where are those entrepreneurs now?

Disappeared – along with permanent mass-employment industries yielding large-scale demand for the UK economy. Will they ever come back?

If not, then the whole concept of work and society needs re-thinking.

This is not so surprising – we left the era where an individual could do R&D behind in most fields a long time ago. We picked the low-hanging fruit.

Krugman’s latest (about the recent IMF report) seems to bear on the investment issue.

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/04/19/crowding-in-and-the-paradox-of-thrift/

It probably doesn’t help that UK workers are so cheap and (with zero hours contracts) flexible to the max. Why invest if you can throw a few more bodies at a problem (obviously this won’t work in all industries) ?

France is an expensive place to employ people – workers have lots of rights and I’m told it’s very difficult to get rid of them. French productivity is higher than ours – probably because employing more people seems to be a last rather than first resort.

Pingback: Tax Research UK » The UK isn’t growing: it’s just working harder and that’s not a strategy

Pingback: Mediamacro myth 8: employment growth | Homines Economici