At the Resolution Foundation’s pay event last week, someone asked a question about immigration. Alison Wolf was leaving but, just as she was on her way out she remarked that, while immigration might not have had an impact on wages, it has reduced the amount of training given by employers.

Well you can’t leave a comment like that hanging so I had a brief Twitter conversation with her afterwards to make sure that I’d heard her correctly. I had. There was, she said, a huge drop in employer training well before the crash and that a link to immigration is consistent with the evidence though difficult to prove with the data we have.

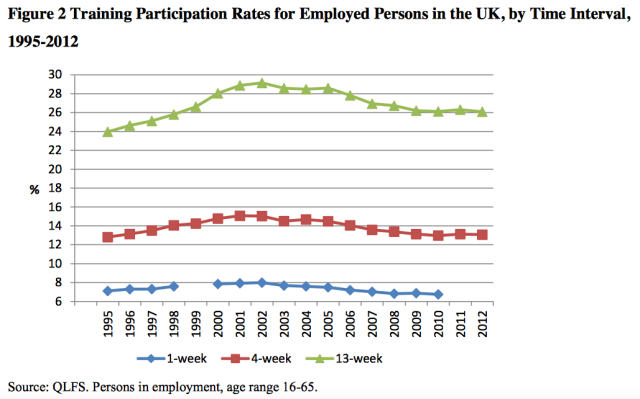

I decided to do a bit of digging. There has indeed been a drop in training provision which started sometime around the middle of the last decade. As this LLAKES report found, since the mid 2000s, there has been a steady fall in the proportion of workers receiving training in the last 13 weeks, 4 weeks and 1 week.

Consistent with this, per capita real terms training investment has fallen by around a seventh:

The best data source for cost indicators is the Employer Skills Survey, which estimates that total employer investment in training in England was £33.3 bn in 2005, and £40.5 bn in 2011. Once inflation is factored in, this represents just a 4% increase, and since the workforce expanded during the interval it represents a real terms cut of 14.5% in training investment per worker.

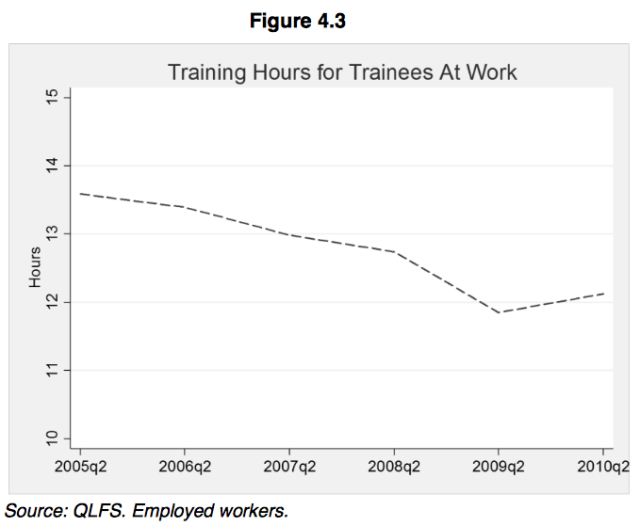

A UKCES report in 2013 found that the decline in training started well before the downturn. It pointed out that, as well as the participation rate falling, even those who were given training spent less time doing it.

The recent UKCES Growth Through People report found that training had declined for all occupational groups since the mid 2000s. The fall was less sharp for the Labour group of occupations (process, plant and machine operatives, and elementary occupations) though it started from an already low base.

At around the same time that employer training provision began to fall, there was also a rise in immigration. It is well-known that there was a surge in immigration after 2004 when the Eastern European countries joined the EU but figures from the House of Commons migration briefing published in February show that migration from the EU15 also rose after 2005. Immigration had also been rising steadily for the previous five years.

The decline in training occurred over a similar period to the rise in immigration so it is possible there might be a link. There is something else to consider here though.

At about the same time, the labour force participation rate of the over 50s began to rise too. According to Ernst and Young, the increasing state pension age and the squeeze on future pension income has forced a lot more people to keep working. This, say EY, together with immigration, has been the main reason for the growth of the labour supply.

Migrants and the over 50s have something in common. They have already acquired skills and experience of the workplace. The Migration Advisory Committee found that migrants, even in low skilled occupations, are more likely to be over-qualified for their jobs than natives. In other words, like the over 50s, to some extent they come to employers ready-trained.

I’m reminded of a conversation I had with a senior executive a few years ago who remarked, “We are drinking from wells that other people have dug.” Whether those wells were dug decades ago in the UK or more recently elsewhere in the world, UK employers are able to freeride on training that has been paid for by someone else.

But this is all circumstantial. Just because some lines on graphs go in roughly the same direction it doesn’t prove cause and effect. The decline in training might be caused by something else, or may simply another symptom of wider falling levels of investment. Or it might just be a coincidence. There is no conclusive evidence that employers are cutting back on training because they have a steady supply of well-trained people. It might look that way but there is no smoking gun. Unless, of course, you know different.

Reblogged this on sdbast.

Interesting and plausible.

It goes to a problem that’s been around as long as I can remember (I’m nearly 60) and am sure as been around since Noah. How to square the circle of you people not being able to get a job because they have no experience* and not being being able to get experience because they can’t get a job.

I also wonder how much the NMW comes in to play here. If an employer has to pay more than a job is worth, in an economic sense not that the person doing it is worthless, they might as well get someone who is overqualified if they can. Also, people who are over qualified might be more inclined to take a job that could be seen as beneath them if it pays more. As observed above this is particularly the case for immigrants where even on the NMW they might be getting a better standard of living than in the country they migrated from. Foir the over 50s it might be a case of doing that job at the NMW rather than not doing anything but at a lower rate they might opt for leisure.

Of course if we had full employment this wouldn’t be the case, assuming that full employment matches jobs to qualifications and experience, something I think is unlikely given technology changes.

*I’m talking here about experience not qualifications.

Whatever the cause(s), it does not bode well for the future.

Interesting hypothesis. Ordinarily we might expect that immigrants would need more training since they’re turning up to an unfamiliar country with different work practices and requirements. The classic immigration wage assimilation story is one where the newcomers initially earn less than similarly qualified natives then gradually converge with them after some period of time. But I suppose what you’re arguing is the “similarly qualified” bit fails here in that it might take less time to train up a Polish graduate to operate the espresso machine and the till than a British non-graduate. I would have made a similar argument about older workers needing more (re)training particularly where IT is concerned. But what older workers and well-educated migrants almost surely bring in abundance is those less-easily observed, softer, work-ethic type skills. If that makes them more “trainable” then there are two competing effects: (i) firms might think they are a better investment for the future and so are more likely to give them training; (ii) they might take less time to train to get to a specific level and so require less training in total than a native. On the other hand there is always a probability of return migration for immigrants and older workers have to retire sometime both of which reduce the potential return on training investment.

Immigration will have an effect, but this is less to do with the quantum increase in migration due to the A8 and more to do with the existing E15. The A8 immigrants are often over-qualified, but that means that they’re often doing jobs that employers wouldn’t expect to spend much training money on anyway. I suspect the quarter of million French have had more of an impact on the training figures than the half a million Poles.

The decline of training is a logical consequence of the free movement of labour in the EU and the performance of the UK economy relative to the E15 in the decade prior to 2008. In other words, it’s a design feature. The flattening out in the training rate since then may reflect the slowdown in migrant flows and the dissipation of labour-hoarding, but the failure of the rate to pick up probably also reflects the fact that the recent job creation “success” of the coalition government has been biased towards low-skill and self-employed roles.

Another factor to consider is the gradual change in the composition of the economy. Some high-tech industries, which routinely invested a lot in training, such as oil & gas, are now in decline. While manufacturing is just about holding its own in terms of value, capital-labour substitution (i.e. higher productivity) means that headcount continues to fall, so the quantum of high-skill training days reduces. Service industries tend to invest less in formal training (and apprenticeships) and rely more on “on the job” coaching.

In the 1960s, through a combination of day-release and evening classes, local FE and HE colleges offered part-time tuition leading to qualifications like ONC and HNC in various areas, along with professional diploma courses – all at a very affordable cost.

Most employers then were and, probably, now, are prepared to support employees in attending day-release classes and/or help with the financial cost of courses but they will not want to have to provide direct training of employees themselves, unless they are a very large organisation.

As a retired college lecturer, I ran evening classes in the 1990s but the level of activity has, I think, declined since due to much higher enrolment costs associated with FE college provision.

Of course, that was also an era when local government fulfilled a role in providing support for academic and vocational training among members of its local community. Not any more….

I came through that period and undertook day release at local College of Technology and evening classes progressing from City and Guilds to HND.

It was not easy but it was affordable with success being rewarded by reimbursement by my company who I think got a tax break by doing it.

Unfortunately an era long gone.

Australia has become home and for the last ten years I have been teaching training assessing in a public (Government Federal /State funded) FE institution.

If one is not a subsidised student (apprentice) then the costs to undertake vocational training have become prohibitively expensive in that time.

Reblogged this on Apprenticeship, Skills & Employability..

Is the NHS an example of that fact? Since they can find a steady supply of overseas qualified nurses etc. NHS regularly trains fewer than will be required?

Suspect the constuction sector might also be an example. Trained few and even before 2008 qualified plumbers, plasterers were coming in from EU.

Doesn’t the NHS regularly train too few nurses and doctors because it can rely on a steady stream of overseas trained recruits?

Suspect the construction sector might also be an example. Training low even pre 2008 and a steady stream of overseas plumbers and plasterers.

Reblogged this on Lost and Desperate and commented:

Cause doesn’t equal effect but this is a super read.

Interesting. Speaking from an industrial viewpoint, quite a lot of training is mandated by PUWER regulations (etc). the day when you employed someone and then let them loose on, or anywhere near, a machine/shop-floor has long gone.

There are a lot of regulations to be considered, and many exist, in nearly the same form, in other EU countries (indeed, many are mandated by EU directives (and many EU directives are as a result of other international organisations directing them).

You cannot even put up plastic bollards directing traffic without training and qualifications (New Roads and Street Works Act 1991), and that applies to imported labour.

(NRSWA Courses are 5-day-700-quid)

Given that taking someone on, untrained to, for instance, put up diversions signs/traffic lights/cones, can cost you several thousand pounds in training…..and then they have to be registered in something like CSCS (etc)………………….