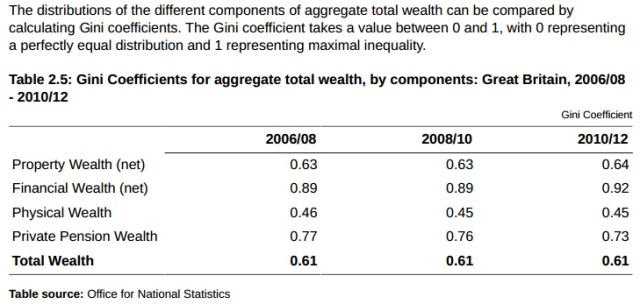

John Rentoul wrote a piece yesterday saying that inequality hasn’t increased in recent years. He does that every so often. Using a chart from yesterday’s ONS report on Wealth in Great Britain, he showed that the Gini coefficient for total wealth has not moved since before the recession.

But Declan Gaffney spotted this, in the same report:

In 2010/12 the wealthiest 20% of households had 105 times more aggregate total wealth than the least wealthy 20% of households. In comparison, the wealthiest 20% of households had 92 times more aggregate total wealth than the least wealthy 20% of households in 2008/10.

If the top 20% have a higher multiple of wealth compared to the bottom 20% than they did four years ago, doesn’t that mean that inequality has increased?

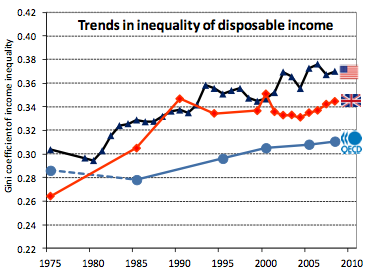

A similar question applies to incomes. John Rentoul is right that there has been very little change in the UK’s Gini coefficient since the 1990s. Inequality, as measured by the Gini, has increased across the OECD but the UK was a trailblazer. We’d got most of our rise in inequality over by the 1990s and others just played catch up.

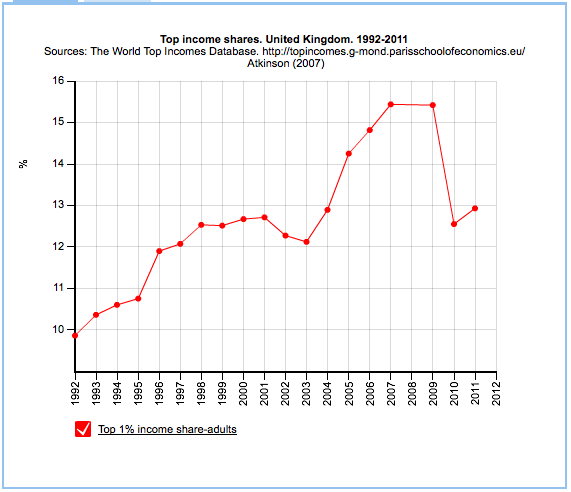

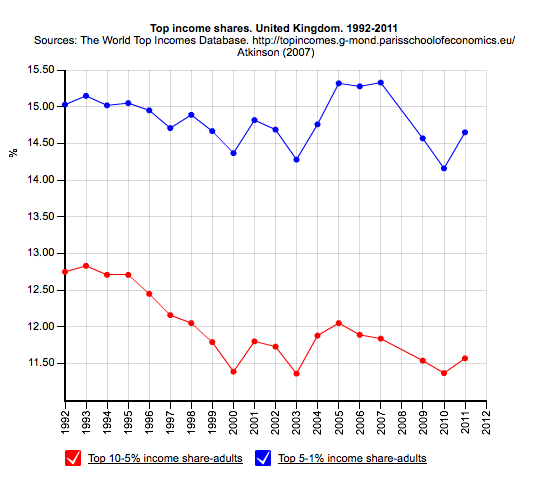

Yet even as the UK’s income Gini coefficient was flat, or even reducing slightly, the share of income of the top 1 percent rose steadily in the 15 years before the recession.

(Chart from World Top Incomes Database.)

The Gini coefficient is only one measure of inequality and its limitations have been discussed at length elsewhere. Small groups can pull away at the extremes without affecting the overall Gini figure.

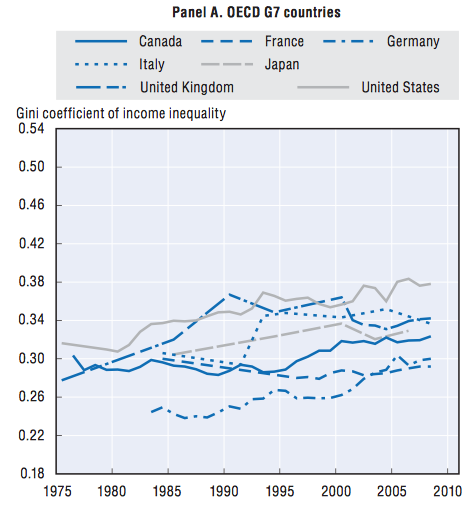

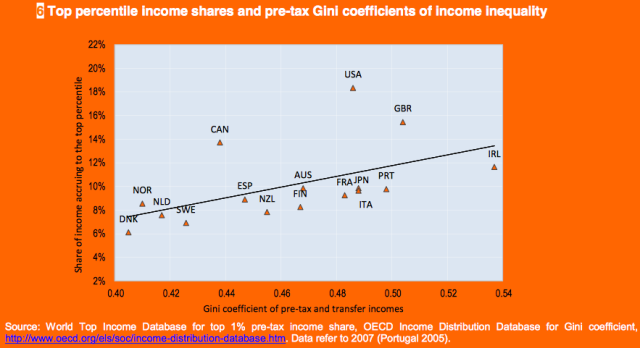

This OECD chart from its recent report on top incomes illustrates the point.

It is possible for countries to have similar Gini coefficients but widely different income shares for the top 1 percent. As the report points out, as a measure, top income share has its weaknesses too as it doesn’t tell you much about what’s going on in the middle and at the bottom. Combining the two measures is useful, though. Whatever measure you use, it’s clear that, before the recession, pre-tax income inequality in the UK was higher than that of most of our comparator economies. (Germany also has a high pre-tax income Gini but seems to be missing from this chart.)

In recent years, and well before Piketty mania, there has been a lot of interest in the rising incomes of the top 1 percent. I wonder if some of this is because their neighbours in the adjacent income decile have started to notice the results. As the top 1 percent’s share rose, that of those in the next ten percent began to fall.

Decline of the middle-class articles appeared in the broadsheets as people found themselves priced out of things they once assumed they would be able to afford, like central London houses, private schools, health insurance and second homes on the coast of Cornwall.

Affordability of property for households with incomes at the 95th percentile

See the whole fascinating map at the FT site.

As Archie Bland said last week, a lot of the writers of such pieces are not actually in the squeezed middle, they just think they are. Most people have no idea how low median incomes are. The squeezed middle angst from people who are still in the top income decile has much to do with their diminishing income and wealth relative to those at the very top.

Is the rise of the top 1 percent just a concern for the envious upper middle-classes then? Does it matter that the incomes of a small group of people are pulling away from those of everyone else?

Perhaps not in the short-term but over time, wealth leads to power. In 2012, Canadian MP Christya Freeland wrote Plutocrats: The Rise of the New Global Super-Rich and the Fall of Everyone Else. Drawing on the model from Acemoglu and Robinson’s Why Nations Fail, (see previous post) she warned of an extractive elite using the state for its own ends.

The story of Venice’s rise and fall is told by the scholars Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson, in their book “Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty,” as an illustration of their thesis that what separates successful states from failed ones is whether their governing institutions are inclusive or extractive. Extractive states are controlled by ruling elites whose objective is to extract as much wealth as they can from the rest of society. Inclusive states give everyone access to economic opportunity; often, greater inclusiveness creates more prosperity, which creates an incentive for ever greater inclusiveness.

The history of the United States can be read as one such virtuous circle. But as the story of Venice shows, virtuous circles can be broken. Elites that have prospered from inclusive systems can be tempted to pull up the ladder they climbed to the top. Eventually, their societies become extractive and their economies languish.

It is no accident that in America today the gap between the very rich and everyone else is wider than at any time since the Gilded Age. Now, as then, the titans are seeking an even greater political voice to match their economic power. Now, as then, the inevitable danger is that they will confuse their own self-interest with the common good. The irony of the political rise of the plutocrats is that, like Venice’s oligarchs, they threaten the system that created them.

Some of you might say this is just liberal leftie blathering but conservatives are starting to worry about it too. John Major recently described the dominance of the wealthy elite as ‘truly shocking‘. In the US, where the top 1 percent have an even greater share of the wealth and income, there is concern too. Here’s Andrew Sullivan, one of America’s most prominent conservative bloggers:

When societies grow more unequal, commonalities fray. Wealth accumulates among the few, who begin to see the polity as something to be used for private interests rather than engaged in for public-spirited reform. But as wealth at the top grows and grows, and as more and more of the middle class attempt to become part of the super-wealthy club, the loss of economic demand among the increasingly struggling majority puts a crimp in the social mobility of the wannabe elites. So we have a wealth glut: hugely wealthy one-percenters and a larger group of under-employed or unemployed professionals. It’s from these disgruntled elites that you will get the tribunes of the new plebeians. And they will be guided by revenge just as destructively as the top one percent is now guided by naked self-interest.

In this video, he explains why he used to be indifferent about inequality, why he isn’t now and why he doesn’t regard concern about the soaring incomes at the top as left-wing. Andrew Sullivan, like many conservatives in the old tradition, has a deep fear of social disorder. In that context, worrying about inequality, and the concentration of wealth among a small elite, makes absolute sense.

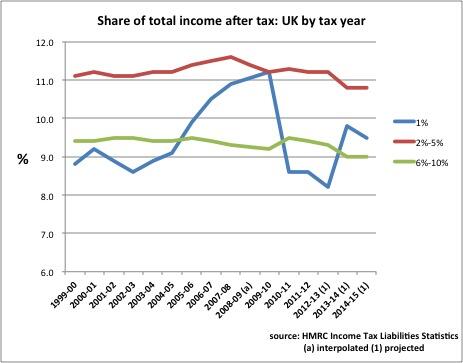

Update: Michael O’ Connor has produced this graph from HMRC figures and projections. The numbers are slightly different from those of Piketty et al, but the pattern shows the top 1 percent income share recovering after the recession, while that of the ‘just belows’ is in steady decline.

Reblogged this on sdbast.