A couple of articles in the Economist upset a lot of people at the weekend. The paper suggested that there was no point in trying to save some of Britain’s former industrial towns. Instead, they should be allowed to decline and the people living in them should be helped to move elsewhere.

The articles (here and here) highlighted the lesser-known geographical divide in Britain. Much has been written about the North-South divide (or, more accurately, a distance from London divide) but there is also a gap opening between the larger cities and the smaller towns, especially those that were once industrial centres.

Whereas over the past two decades England’s big cities have developed strong service-sector economies, its smaller industrial towns have continued their relative decline. Hartlepool is typical of Britain’s rust belt in that it has grown far more slowly than the region it is in. So too is Wolverhampton, a small city west of Birmingham, and Hull, a city in east Yorkshire.

As the industries that created them disappeared, many towns were left high and dry. Inevitably, those with skills and qualifications used them as a route out, contributing to further decline. As the Economist notes:

Fully 22% of people in Wolverhampton have no qualifications—against a national figure of 9%. As in Hull and Hartlepool, while not all the local schools are bad, their overall performance is appalling.

And even with growth, the most ambitious and best-educated people will still tend to leave places like Hull. Their size, location and demographics means that they will never offer the sorts of restaurants or shops that the middle classes like.

A report for the European Commission said something similar:

These sorts of regions tend to suffer the problems that go with intractable unemployment and economic restructuring.

They often contain pockets of long-standing high unemployment especially among young people and older men. Poverty and social exclusion, housing blight and other forms of deterioration in the living environment and urban fabric are widely observed features of these sorts of regions.

Their skill pools have been rooted in the traditional industries – leaving older but potentially active workers exposed to exclusion in the face of an inability to adapt in the face of change.

The trouble is that employers then begin to avoid these places, put off by poor skill levels and social problems.

I wrote about this a couple of years ago, after Victoria Wood had commented on the quick-witted vibe she got at gigs in large cities, compared with the the slowness of audiences in the smaller towns.

It reminded me of a conversation I had about relocation with an HR director which, I suspect, is typical of a lot of employers’ attitudes. I have disguised the names of the places under consideration, one a big city with a vibrant centre (let’s call it HubCity) and another in former smokestack single-industry town (let’s call it Coketown). The organisation had offices in both places and wanted to expand one, potentially as a new HQ.

This is how our discussion went:

We need to get our operations out of the south-east. We should have done it years ago. The property costs and wages are killing us. Expanding the HubCity office looks like our best option. Wages are lower and property is a lot cheaper.

“But surely salaries and property costs are even cheaper in Coketown,” I replied.

Well they are but we just can’t get the quality of people in Coketown. HubCity has two universities and a lot of colleges. The people are just better educated, more sophisticated and come with a better attitude.

We have tremendous problems in Coketown. The older ones were used to working in industrial plants and even the younger ones, who didn’t, seem to have inherited the same attitudes. Coketown has huge social problems and people bring them into the office. We spend a lot of time trying to manage those problems. By locating ourselves in the middle of all that, we’ve taken on lot of aggro that we didn’t anticipate.

In other words, although salaries and property were cheaper in the old industrial town, the lack of skills and the social problems of the area meant that there would be a hidden overhead to setting up there. In the shiny regional capital, with its universities and colleges, there was a pool of keen, well-educated people who would be a much more productive much more quickly.

You can see the effects of this in the regions outside the South-East. Cardiff, Manchester and Newcastle have their stunning new developments and you can tell there are people there with plenty of money just by walking around. Go a few miles up the road, though, and you will find blighted and boarded up small towns. It doesn’t matter how cheap they are, employers are avoiding them. The worse they get, the less likely firms are to relocate. The lure of cheaper property and wages only goes so far. It may tempt organisations away from the South-East but only to the larger regional capitals. Small town Britain is a step too far.

There’s another potential problem brewing in the small towns though.

Time for another story. Four years ago, my father-in-law died and I went to South Wales with my wife and brother in law to help sort things out. While they were meeting the solicitor, I waited for them in a nearby pub. It was 11.30am on a wet Tuesday in February and already the place was filling up. By lunchtime it was buzzing. The clientele were predominantly in their 60s and early 70s.

My father-in-law used to joke that it was the pensioners not the teenagers who did most of the drinking in the town. The pubs and the working men’s club did a roaring trade. The youngsters rushing around with food and drink orders had cause to be grateful. As long as the pensioners were spending, their jobs were safe.

Where was the money coming from? I only have my father-in-law’s take on this but many of them, he said, were retirees from the old nationalised organisations or the big industrial firms. The pension funds of the railways, the gas industry, British Steel, Ford and BOC were providing a steady stream of cash for the local economy.

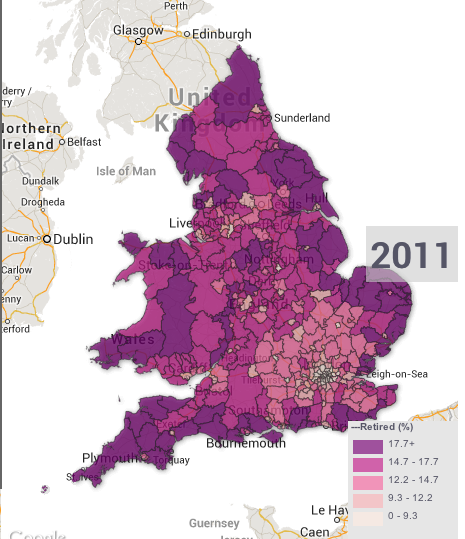

I couldn’t find any data to back up his hypothesis and I’m not sure how you’d get it but if you look at the distribution of pensioners, they are concentrated well outside the major cities, with areas like the old mill-towns and South Wales having relatively high numbers.

Source: ONS Census data

How many small towns are being kept afloat not just by state spending but also by the legacy payments from the industries in which their inhabitants once worked?

Most of those generous pension schemes have now been closed down. The retirees of the future will not have as much money to spend. Given the employment patterns in some of the smaller industrial towns, many may not have had as much chance to save either. Fewer of them will be loading up the car in Morrisons then popping down to JD Wetherspoon for a pub lunch on a Tuesday. That means fewer jobs for the youngsters and, probably, a speeding up of the brain drain to the larger cities.

Add to that the disproportionate dependence on state benefits in some of these areas and the situation starts to look even grimmer. According to a Sheffield Hallam University study quoted in the Economist, the government’s social security cuts will take round £700 per year out of Burnley, Hartlepool and Merthyr Tydfil for every working age resident.

I can’t comment on the Economist’s assessment of Burnley and Hartlepool as I don’t know enough about the economy in either town. I was a bit surprised to find Hull, with a quarter of a million people and a long-established university on the Rustbelt Britain list.

However, while many people in the places mentioned may have felt insulted, there is a question about the economic viability of some of Britain’s towns. Without considerable state support, the future for many of them looks bleak. Benefit cuts and falling pensions are likely to take even more money away from their ailing economies.

The Economist editorial said the subsidies, tax breaks and other incentives should stop and that Britain’s old industrial downs should be left to shrink, or even disappear completely:

Place and community are important. But new communities can be created in growing suburbs fringing successful cities. It has happened before. The towns that are now declining were once growing quickly, denuding other settlements, often in the countryside. The Cotswolds were the industrial engines of their day. One reason they are now so pretty is that, centuries ago, huge numbers of people fled them.

That’s true but the inhabitants of today’s declining towns have something the nineteenth century Cotswold folk didn’t: Votes. Allowing towns to wither and die now has political consequences. It may be some time before we see coach-loads of Chinese tourists visiting the picturesque North Sea village of Hartlepool.

Pingback: What future for Britain’s ‘rustbelt’ towns? - Rick - Member Blogs - HR Blogs - HR Space from Personnel Today and Xpert HR

Interesting point about pensions and pensioners. Intuitively feels right for this part of Dorset but it’s mainly retired professionals moving out of cities. The map seems to indicate that as well. This of course brings higher health and social security costs.

A point the Economist made that you seem to have glossed over is the poor transport links to places like Hull. I’m not sure that could be fixed in time to save the towns if indeed it could, but needs some investigating.

It also points to another major problem. It’s not that we have a housing shortage, boarded up streets in Hartlepool were mentioned, but we have a shortage where people want to live.

All in all another argument for you post about moving Government out of London.

Wait a minute, lots of people who currently live in London because they need to work, would like to live elsewhere. So it’s not that we have a housing shortage, but we have a shortage of jobs in places where there’s housing.

The whole question posed by the Economist does of course assume the primacy of economic forces over any others. The logical conclusion is that we should demolish the rust belt towns, rip up the housing to reclaim the farmland, and build London ever bigger. Never mind what the public think, they don’t count.

You might want to have a look at our recent report looking at the geography of jobs within cities, and adds another layer of analysis on large cities and medium and small cities. In short, city centres in large cities are becoming increasingly important, while the opposite is true in medium and small cities.

There is nuance to the story however. Smaller places such as Brighton have bucked this trend, while Sheffield has ‘hollowed out’, with its city centre losing jobs while out of town sites have created them.

Click to access 13-09-09-Beyond-the-High-Streets.pdf

One of the reasons the centre of Sheffield hollowed out was because of the policies of the Conservative government under Margaret Thatcher. They deliberately moved all investment to the eastern side of the city under the rulings made by Sir Hugh Sykes as head of the development organisation they set up, whilst the city council were starved of funding. It has come a long way since then but did make a disastrous decision to believe the promises of private developers to revamp the city centre and set about compulsory purchase of many of the shops and businesses there as part of the deal. The development has not yet come off and this has also influenced the centre, so I don’t think it is as clear as you suggest.

Policy has had a role to play in the geography of jobs in many cities, enterprise zones like Meadowhall being a prime example. Have a look towards the end of the report where we show how policy has contradicted itself, implementing Town Centre First at the same time as creating enterprise zones and subsidising business parks.

It’s interesting that exactly the same comments were made about Liverpool in the early 1980s after the Toxteth riots – that the City should effectively be abandoned as it was in terminal decline and geographically in “the wrong place”. Compare that to now, where it’s been massively regenerated (primarily with EU support) and is a bustling, thriving city with a lot going for it. So perhaps it’s a lack of will among policy makers that’s contributing to the decline of smaller towns (and Hull – which as the poster above notes needs decent transport links to improve its prospects)

Pingback: Demise of the Global City

Pingback: Demise of the Global City - Pacific Standard: The Science of Society

Left Hull 50+ yrs ago. At that time Hull was in the bottom three educational authorities for the whole of the U.K. Today still in the same situation. Throughout these years it has had a Labour controlled council.

That map of retired people as a percentage of the total population seems eerily like the map of the EU referendum results, with London, much of its northern and western hinterland, and the cities of Newcastle and York (but not their surrounding areas) voting Remain and having a younger population profile than the rest of Leave-voting England.

It has even been suggested that the anxiety about migration that prompted the older generation to vote Leave may have been as much about internal migration as about foreign immigration.

Are there any statistics of the regional EU referendum vote that are broken down by age cohort? Those would be very interesting to look at…