The HR director at an organisation I worked with a few years ago, commenting on people’s refusal to engage with change until the last minute, said: “When a decision is announced in this place it’s a signal for the debate to start.”

I was reminded of this when I read Heather Rolfe’s report on employer responses to Brexit, in which a number of employers commented that there had been more workplace discussion of the referendum since it happened than there was before it:

While referendum discussions were described as fairly limited before the vote, levels of interest were considerably higher after June 23rd. The surprise of employers was shared by employees and accompanied by a good deal of informal discussion, often focused on free movement issues. The manager of a hotel chain described how this included ‘concern around whether the people are wanted in the UK’. Some respondents felt it was ironic that interest in the referendum and in the EU was higher in the aftermath of the vote. The HR director of a food manufacturer stated:

‘My disappointment from people generally is if there’d been that level of discussion and engagement prior to the Referendum… perhaps the outcome might have been different’.

The shock among the employers surveyed is a reflection of how dependent they are on workers from the EU. The possibility of a reduction in their labour supply fills them with horror.

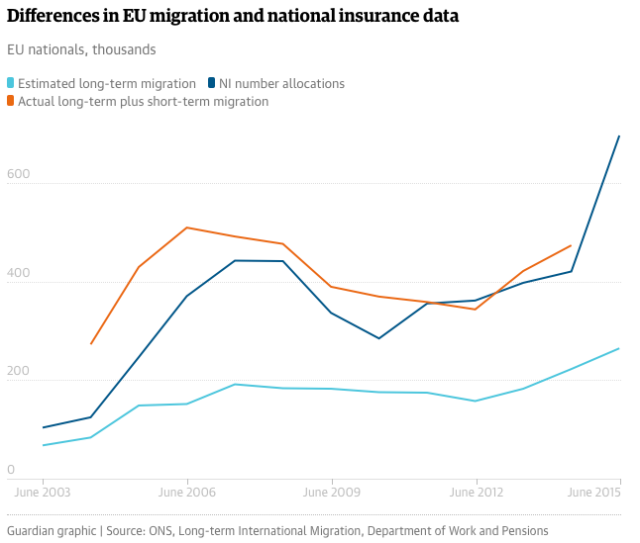

For over a decade, the UK economy has been built on the assumption that there is a massive pool of flexible labour available. Free movement rules and geographical proximity mean that the EU migrant workforce is highly responsive to changes in the economy. People come and go according to how many jobs are available. As the ONS migration statistics show, migration from the EU tailed off during the recession and then picked up again as the economy recovered.

At the same time, many of the EU migrants already here went home (or somewhere else) when the economy crashed and the work dried up.

While these charts only cover migration of more than a year, we also know, thanks to Michael O’Connor and Jonathan Portes, that there is a considerable churn of short-term migrants from the EU. The difference between long-term migrants and the number of NI allocations shows that a lot of people come to the UK to work for short periods.

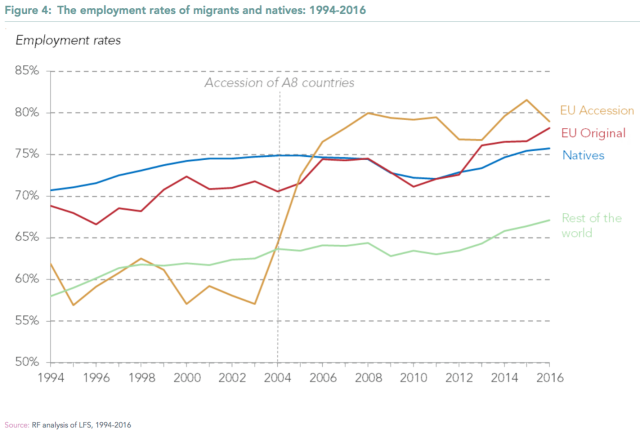

As the Resolution Foundation’s recent report on migration and the labour market showed, the employment rate among EU migrants has tended to be higher than for the UK born, and is especially high for those from eastern Europe. Furthermore, their employment rate recovered more quickly after the recession. This is due, in part, to their mobility. When there is more work, more of them come. When there is less work, fewer come and more leave.

From an employer’s point of view this is great. There is a ready supply of labour, much of it highly qualified, that responds quickly to changes in demand. When you want more people they arrive. When you don’t need them any more they go home.

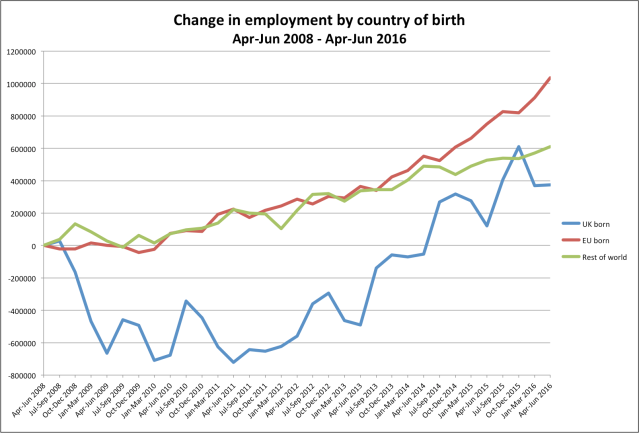

Around half of the net increase in employment since the recession has been due to EU migration.

Source: ONS EMP06, 17 August 2016

It is disingenuous of politicians to boast about the ‘jobs miracle’ while, at the same time, demanding a reduction in immigration to under 100,000. Many of these jobs would probably not exist without the ready supply of EU migrants. As the Resolution Foundation research shows, entire sectors are now dependent on labour from the EU and it is unlikely that UK-born workers will take these jobs over should they leave.

It is unlikely that native workers will totally fill the gap at current wage rates. Pay in these sectors averages £9.32 an hour, significantly below average native wages of £11.09. We know that lots of workers in these sectors are migrants from the EU ‘accession’ countries, whose average earnings are £8.33, £2.76 below that of natives. With employment at an all-time high it is unlikely that there are large numbers of natives either looking for work that will be attracted to these sectors given the low-wages on offer. Similarly these kind of wage rates are currently not sufficient to bring those not in the labour market into participation. It seems unlikely that the simple absence of migrants would be enough to change that situation.

Sarah O’Connor wrote about the potential impact of the end of free movement on the food industry:

Have you ever noticed how supermarkets run out of fruit salads on sunny days when everyone decides they fancy a picnic? No? That’s because they rarely do.

I never really thought about the mechanics behind this until I interviewed a man who supplied temp workers to a British company that made bagged salads and fruit pots. Demand would fluctuate according to the weather, but British weather is notoriously changeable and fresh products have a short shelf life. So the company would only finalise its order for the number of temps it required for the night shift at 4pm on the day. Workers on standby would receive text messages: “you’re on for tonight” or “you’re off”.

Most of this hyper-flexible workforce had come to the UK from Europe. “We wouldn’t eat without eastern Europeans,” the man from the temp agency said confidently.

And there are many good reasons why the locals won’t take over when they are gone.

[T]here are already plenty of jobs for British people. The proportion of UK nationals in work is at a near-record 74.4 per cent, higher than in 2004 when the “A8” eastern European countries joined the EU (which is when migration to the UK began to increase sharply). Torsten Bell, director of the Resolution Foundation think-tank, says the only significant pocket of unemployment left in Britain is among disabled people. “And we’re not about to send them out into the fields”.

There is also something about the nature of these jobs that makes them tough for UK nationals to do. These sectors usually require extreme flexibility from staff: the salad-baggers who wait for a text message to say they have work that night; the cleaners who cobble together piecemeal shifts at dusk and dawn; the fruit pickers living in caravans on farms.

When people say “migrants are doing the jobs that Brits are too lazy to do”, they are missing the point. These jobs may be palatable if you are a single person who has come to the UK to earn money as a stepping stone to a better future. But if you live here permanently, have children here, claim benefits here, they are not jobs on which you can easily build a life.

There you have it. British employers have access to a plentiful supply of Europe’s young, mobile and hyper-flexible employees. We have structured many sectors of our economy on the assumption that there will always be a steady stream of them.

Of course, the supply won’t disappear overnight. As the Social Market Foundation said, by the time we actually leave the EU, a majority of the EU migrants who are already here will have permanent residency rights.

But, as the tap is turned off, the hyper flexibility will disappear. If, in future, EU citizens are subject to the same immigration rules as those from outside the EU, firms that have come to rely on that flexibility will struggle to find workers.

An optimistic view is that this may lead to more investment in technology and training as employers find ways to produce the same with fewer people. Last month, I went to a Resolution Foundation conference on robotics. (The accompanying report is here.) The combination of economists and robotics experts produced some fascinating discussion. One scenario had the post-Brexit labour shortage kick-starting massive investment in technology, with robots picking crops in the Lincolnshire fields and the UK becoming a world leader in artificial intelligence by 2030.

The trouble is, such a re-orientation of our economy would require a complete change in British corporate culture, much of which has been short-termist and reluctant to invest for several decades. The more troubling possibility is that the reduction in EU migration will simply lead to an increase in the number of illegal workers. Should that happen the enforcement agencies would struggle. As the Resolution Foundation warns, their resources are already stretched as it is:

[T]he three existing labour enforcement units have a combined staff of less than 350 – equivalent to one enforcement officer for every 20,000 working age migrants.

These agencies could be given responsibility for enforcing and policing any temporary workers schemes that might be set up in the future, but they are already stretched carrying out their current duties. If temporary labour migration is not to become illegal migration there would need to be significant investment in the future.

Cutting off or even significantly reducing migration from the EU will be a shock to an economy that has been built on the assumption of a plentiful on-tap supply labour. As Sarah said, we have come to take for granted much of the work that the migrants do. We will only really we’ll only really understand that when they have gone.

Perhaps pensioners could fill the gap. Would help solve the Pensions problem.

Great post as ever. I find myself struggling to reconcile passages like this “British employers have access to a plentiful supply of Europe’s young, mobile and hyper-flexible employees. We have structured many sectors of our economy on the assumption that there will always be a steady stream of them.” with the oft-reported finding that immigration has not depressed wages. What would happen if the supply of this type of worker dries up? Won’t part of the response be to restructure the economy to use workers that require higher wages? I mean I guess some firms reliant on these workers will shut down, others will try to find labour by raising wages and manage to survive, no? If so, how can immigration not be depressing wages relative to the counterfactual?

Is there some possibility that Brexit will actually end up raising some wages for some? (I know there are lots of offsetting effects that will depress wages too, I just sometimes wonder if we are not under weighting possibility of immigration having held down wages more than our empirical research told us)

Did you see the Resolution Foundation report on this? And Michael O’Connor’s response? https://medium.com/@StrongerInNos/alphabet-soup-4572da601236#.fkq31hhkp

Resolution Foundation concluded that it probably has depressed wages but not by much and that the hammering the economy is about to take will offset any rise in wages.

Hi, no hadn’t seen that, thanks.

Still, is it fair to say that if impact on wages small, harm done to firms by reduced supply of immigrant workers also small? Maybe not. I can see asymmetry wherein gradual supply of immigrants only has small impact because there is time for the demand they add to economy to feedback, whereas sudden withdrawal is more drastic.

It’s because, as the article points out, migrant workers dominate in sectors where there is no supply of native workers. There are several professions where there are labour shortages but wages are low:

– HGV drivers

– construction

– agriculture

– health and social care

These jobs will always remain relatively low paid because they are industries which rely on narrow profit margins. Any increase in wages will lead to two options. One is that it will lead to an increase of prices, which when applied across the economy, leads to inflationary pressures which reduce any effect of a wage increase.

The second option is that the increase in prices will lead to a reduction in consumption, thus production, reducing the availability of jobs.

So in both circumstances, the jobs exist because there are migrants available to do it.

There is often no supply because nobody trains youngsters anymore. Why would they go to all that bother when they can get a fully-skilled immigrant, delighted with the wages, and eager to work every hour the Lord sends?

The HGV driver shortage is going to be acute in just a few years as a whole generation retires. About the only hope is that the self-driving truck will be with us by then, or that the railways can get their stuff together and shift some freight in driverless trains. Perhaps technology, yet again, will save the day?

«There are several professions where there are labour shortages but wages are low:

– HGV drivers»

http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/aug/02/industrial-failure-uk-lorry-trade-truck-driver-squalor-low-pay-no-unions

«Employers fill gaps with agency staff instead of raising rates. Big haulage firms subcontract work, often sub-sub-contracted down the supply line, each creaming money off, until the job is done by low paying, fly-by-night operators.

I spoke to Mick Johnson, an agency driver from Grimsby, who says he finds eastern Europeans at the bottom of the chain, paid Latvian rates of €1.20 an hour, living in their cabs for three months. His union says some foreign drivers’ bonded terms amount to modern slavery.»

It is likely gangmasters and agencies for these too:

«– construction – agriculture – health and social care»

Lots of “self employed” agency workers around. Another comment in this post adds entirely plausibly «We can get as many [overseas] skilled workers as we need within a few days via agencies». A comment on another blog:

«the super-exploited migrants in Thetford who have been under the thumb of gangmasters recruiting for very low-paid / no-frills jobs in picking, cutting and packing for the just-in-time supermarket demand. Thetford lost 700 jobs with the closure/relocation of the local ‘Tulip’ plant (cutting and packing Danish, intensively-farmed pork) in 2007, just as this chap was starting out. Being migrants herded by said gangmasters most of the 700 were entitled to nothing. Most of the other migrants in the town were in zero-hours-type jobs working until midnight one day, unemployed the next»

There have been reports of gangmasters and agency owners making hundreds of thousands net profit a year, a way to get rich quick.

Immigration has an effect on wages – there wouldn’t be much point to it unless it did. Nobody’s bringing over workers from wherever because they like the cuisine they bring with them, nice though that may be a side benefit. The economic appeal of immigrants is two-fold: in low-skill occupations like fruit picking, they’re cheap, reliable and plentiful, whilst in medium and high-skill occupations.like engineers, doctors and programmers they’re simply available, which in turn means that labour rates don’t rise as much to reflect the scarcity that would otherwise prevail were immigration limited or cut off. From an employer’s point of view, that’s a lot to like in either scenario, and it must surely have been a factor in Brexit with the indigenous workers who voted in large numbers to leave the EU.

Anecdotally, in my manufacturing business, we are under no pressure to give any pay rises and have not been so since 2008. We can get as many [overseas] skilled workers as we need within a few days via agencies, though sadly and inevitably, we’ve seen the total collapse of apprenticeships, the local college has closed its vocational courses and the industry training boards have all closed too. Since we no longer train anyone, its axiomatic that we now rely on immigrants to fill factory floor positions. This is at least part of the argument that we can’t cope without immigration; we have 1,500,000 people claiming the dole who’d all very much like a job, but they’re not equipped or unwilling to do the work available that 1,000,000 immigrants currently perform.

By way of corollary, we’ve given pay rises over the past few years and have some highly paid staff on the shop floor. Those staff are also very productive, and the benefits of paying more than we could get away with are many. Better morale is hard to quantify, but shouldn’t be underestimated, and the ability to pick the best staff from the available pool is also a real benefit. The future lies in automation and capital investment, which in turn boosts productivity, which then boosts wages and growth. In an economy paying workers more than $50 a week, that’s the way ahead.

The issue we face is youth unemployment and the creation of a largely white working class that is being excluded from jobs. That’s really worrying, and if Brexit does one thing, let’s hope it’s to raise the question as to why we don’t train young people any more, and what that does for our future.

Well said….the first thing HMG should do is close the borders…no more immigrants from anywhere unless they really are elite workers…then step two…add 1% on a firms tax bill for every 10 jobs offshored and strip any members of management of any honours if more than 100 jobs are offshored.

Apprenticeships aren’t coming back until the supply of cheap labour is stopped dead.

“let’s hope it’s to raise the question as to why we don’t train young people any more”, because they are not interested to be trained? I myself applied for a few apprenticeships in Cumbria (as a baker, assistant in horticulture and catering assistant) and I was about to be interviewed in all three because no UK-born youngsters had even applied… I was not selected because it came out that those jobs are only for people not in higher education (rightly so, I was so dumb I hadn’t read the small print!) but those apprenticeships kept being vacant. Methinks some low wage worker applied when the apprenticeship position was closed?

So… wouldn’t it be better to 1) convince young people to learn trading, building and hospitality jobs again 2) restrict benefits for all young people unless they didn’t accumulate 2 years (at least) of NICs?

@gunnerbear

“the first thing HMG should do is close the borders…no more immigrants from anywhere unless they really are elite workers”

Beyond the idea being ‘xenophobic’, it is also impossible to achieve. Plus, due to that line of thinking, high skilled job applicants like to think they are welcome in a country, closing borders wouldn’t really do anything in that regard, worse.. it would appear like UK is not welcoming anyone, regardless of skills.

If a Trumpish line of thought would prevail, you will find that the easiest to scare off are the elite workers, not the illegals or low skilled, who have nothing to lose either way.

“Resolution Foundation concluded that it probably has depressed wages but not by much….” The Res. F. should get their arses out of their nice offices and visit some areas like Grimsby and Boston and look at the pay rates there.

The Res. f. is up the backside of the Labour Party – the same party that threw open the gates of the UK to all and sundry……..

An interesting counterpoint is the work done on minimum wage increases?

Another great post, but can I suggest that a crucial factor, beyond whether people feel welcome and/or able to work here may be missing. Migrants, particularly temporary ones, will look at their wages in home currency terms. If we look at how the Brexit vote has affected the international wage levels via the exchange rate, then we can see that there has been a real drop in pay. Examining the wage earned by workers in GBP terms misses the migrants key determinant on whether being in UK makes sense – that is, how much can you take home when your temp work is done. The UK is looking a lot less attractive to the temporary worker because the amount of money you earn in your home currency has dropped dramatically. As a UK citizen working abroad in Czech Republic, the devaluation of that currency a few years back made me reconsider whether staying was still an option. In the UK, we just are not paying what we were only a few months ago. In the short to medium term, this may be far more important than the right to work 2 -3 years down the line. Of course, this is still a fallout of Brexit, but a more immediate one than waiting for Article 50 to be invoked.

Fantastic comment and I agree on all points.

I think there is a vast gulf of mutual incomprehension here. A kind of Maslow’s hierarchy of political needs which is not being properly understood. The assumption of many economists and politicians is that the need they are seeking to meet is a purely financial one. People are consumers, either of jobs, or of goods, and the EU is the best way of meeting those needs. For many people who voted Leave, however, political representation and control is the primary need. A need to be heard, of having their concerns about there nature of the society they live in addressed. Of being able to hold real decision makers to account.

If this was a change programme you would want to see some rigorous analysis of benefits of the various proposals, and to do that you would probably assemble a number of test cases and assess each proposal against each of those test cases. So here are a few.

– opportunities to get a return on investment in one’s own career. e.g. becoming a nurse, a hgv driver, a plumber.

– ability to get treatment in your local hospital on a sensible timescale.

– ability to buy a home.

– ability to walk down your street and know that the people you pass are just as committed to a peaceful prosperous neighbourhood as you are.

– ability to influence political decisions that influence you and your family’s future through democratic means.

– ability to buy fresh salad leaves in your local supermarket on a hot summer’s day.

The way Leave/Remain influence these issues is not straightforward but it might give a more rounded view of issues than simply whether GDP goes up or down.

Excellent point. The mistake the Remain campaign made was almost always focussing on the economic issues when forgetting to become involved in other concerns voters had. This was not an election when they could triangulate on expected voting intentions. eg Older voters in the Home Counties allied with those in social housing in the North East in a way not contemplated by the Remainers. If they had dealt with concerns about changes in society due to increased immigration, impact on services/wages rather then leaving the field to the Brexiteers they may well have been succesful.

The Remainer’s couldn’t talk about immigration policy failures or the damage done to communities by massive, uncontrolled, immigration…..

…because it was the Remainac’s that engineered that very crisis…..

Anyone who voted Leave because they hoped it would make housing more affordable was living in cloud-cuckoo land, because surely they noticed that two of the most rabidly pro-Brexit newspapers (the Express and the Daily Mail) were also the two most notorious for celebrating increases in house prices.

Brilliantly put……

….bit like all the s**t talked by the scum in the HoC about bringing back Apprenticeships….

….Apprenticeships will never return on a large scale so long as UK firms are allowed to import cheap labour or export UK jobs without penalty….

Great article. The one thing I don’t see in the commentary overall is that a shortage of staff in certain sectors will lead to a shift in consumer tastes. As a British immigrant into Switzerland where the wages are much higher in the UK items which demand high labor like your pre-washed salad example are pretty rare in shops. A sandwich in a supermarket will cost from £5 or an individual salad portion at least this. Hence there are few available. Prices of the basic but less prepared products are much cheaper and more available.

Makes no difference to BoJo or Liam what happens. Like them, those in charge are ‘hand wavers’, never having had implementation responsibility or experience they just say ‘do it and it will be OK’. Reality does not touch them.

Which raises the question – who benefits from Brexit. What intelligent people would drive forward the idea given that a good number of well qualified people reckon it is a disastrous idea. Pretty clearly the white working class who voted out are not going to benefit, stuff is going to cost more and their wages are not likely to go up much if at all.

But some of the establishment types might benefit in that lack of human rights legislation will make keeping people compliant easier. Prisons and the justice system could become less expensive and politically troublesome. Similarly low wage and zero hour contracts and poor but rented housing might benefit the rougher kind of employer and rentier. Lower tax receipts might become an excuse to cut back services including health. Overall the benefit to them is an easier life and more profit, the benefit to us is a nastier place to live in.

As for the need for migrant workers. Of course this will not go away and government will underfund the labour enforcement agencies and migrant workers will be a fact of life vigourously denied.

The interesting thing will be when the politicians wake up to the enormity of the problem, but I fear that fudge and muddle will prevail, no-one can be made to look idiots however much it costs the British people.

«however much it costs the British people»

But “British people” are not impacted in the same way by low-wage immigration. For example upper-middle class property owning southern english rentiers are enthusiastic about it: it means bigger property prices, bigger rents, cheaper cleaners, shop assistants, gardeners, carers, etc.; they just outraged that the foreign hired help instead of keeping to some isolated ghetto dare to show themselves in public presumptuously thinking that their EU citizenship entitles them.

«The more troubling possibility is that the reduction in EU migration will simply lead to an increase in the number of illegal workers. Should that happen the enforcement agencies would struggle.»

«As for the need for migrant workers. Of course this will not go away and government will underfund the labour enforcement agencies»

Indeed! their budget will be cut and they will be told to just signoff the paperwork without questioning it, to maintain appearances. Just like in the USA. Enforcement does not “just happen”, it happens if there is a political will behind it.

«migrant workers will be a fact of life vigourously denied.»

Indeed. The obvious solution to a possible undersupply of desperate, young, cheap, labour market competitors from eastern Europe for lazy, uppity, expensive northeners and scots is not just illegal immigration and is pretty obvious: large numbers of “guest workers” from third world countries like Burma or Mauritania on “temporary work permits”, so they won’t be counted as immigrants and have none of the legal and civil rights of EU citizens; passport confiscated on arrival, and mandatory residence with curfew in low cost sheds, out of town, out of sight of the middle classes. That’s the goal of the Brexit leadership. It is the Dubai/Kuwait approach.

It is also the goal of a significant part of the “left”: since EU immigration is much easier currently than from the rest of the world, from places like Mauritania, and the EU is nearly entirely white, and the rest of the world is mostly darker skinned, they describe EU immigration as racist, because it privileges white immigrants over darker skinned ones.

There will also be more offshoring. A commenter on another blog reported this very plausible story:

«I once saw a business spot on the BBC World News in Germany where they showed the British embassy in Vietnam hosting visits for UK business leaders to see how they could improve profitability by outsourcing to Vietnam»

Please note carefully: this was not organized by the vietnamese embassy in the UK, but by the UK embassy in Vietnam, no doubt as instructed by the Foreign Office, and no doubt by the Treasury and prime minister’s office.

“The possibility of a reduction in their labour supply fills them with horror.”

So near yet so far, I think the author meant…

“The possibility of a reduction in their supply of cheap labour fills them with horror.”

«The more troubling possibility is that the reduction in EU migration will simply lead to an increase in the number of illegal workers. Should that happen the enforcement agencies would struggle.»

Should that happen their budget will be cut and they will be told to just signoff the paperwork without questioning it, to maintain appearances. Just like in the USA. Enforcement does not “just happen”, it happens if there is a political will behind it.

Anyhow, the bigger solution to a possible undersupply of desperate, young, cheap, labour market competitors from eastern Europe fort lazy, uppity, expensive northeners and scots is not illegal immigration and is pretty obvious: large numbers of “guest workers” from third world countries like Burma or Mauritania on “temporary work permits”, so they don’t count as immigrants and have none of the legal and civil rights of EU citizens; passport confiscated on arrival, and mandatory residence with curfew in low cost sheds, out of town, out of sight of the middle classes. That’s the goal of the Brexit leadership. It is the Dubai/Kuwait approach. It is also the goal of a significant part of the left: since EU immigration is much easier currently than from the rest of the world, from places like Mauritania, and the EU is nearly entirely white, and the rest of the world is mostly darker skinned, they describe it is racist, because it privileges white immigrants over darker skinned ones.

Plus more offshoring. A commenter on another blog reported this very plausible story:

«I once saw a business spot on the BBC World News in Germany where they showed the British embassy in Vietnam hosting visits for UK business leaders to see how they could improve profitability by outsourcing to Vietnam»

Please note carefully: this was not organized by the vietnamese embassy in the UK, but by the UK embassy in Vietnam, no doubt as instructed by the Foreign Office.

So according to Sarah O’Connor, without Eastern Europeans, people in the UK would be forced to peel their own bananas. The horror! And this is because natives have plenty of work, which is why so many of them are desperately self-employed at below subsistence incomes.

Thank you, Rick, for pointing out yet more sloppy thinking and prejudice in the media.

I take your point about corporate short-termism, but nearly all of the bits and pieces needed to put together agricultural robots already exist. It’s just a matter of putting them together. Don’t the English have a word for ‘entrepreneur’?