The news was all about Rochester and Dan the flag man last week, so the National Audit Office report on local government finances didn’t get much of a look in. There was a bit in the Guardian and Russia Today found the space to report that half of UK councils face financial collapse but otherwise, the empty noise of the culture wars dominated the headlines.

The NAO’s report explains how much local government funding had been cut and where the cuts have landed. As I found out when I wrote something about this a year ago, there isn’t much information available. One of the NAO’s findings was that, while the government may be cutting public service spending, it has no idea what services are being stopped or run down because it has contracted most of the cutting out to local authorities and isn’t keeping track of what they are doing.

As you might expect, the picture is bleak. The NAO reckons that, by next year, council funding will have fallen by an average of 37 percent in real terms since 2010-11. For metropolitan districts, that rises to 41 percent. Of course, the population has risen since then, so the per capita amount will be larger still.

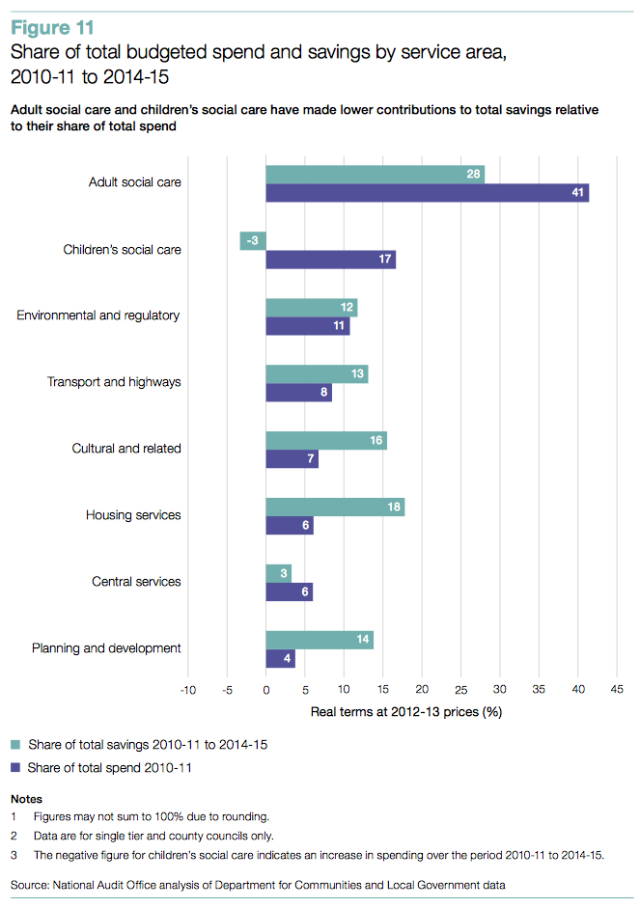

In response, councils have cut spending on services. These two charts show where the axe has fallen. It’s useful to look at them both together. Figure 10 shows the percentage reduction for each service area. Figure 11 shows the share of the cuts.

Planning and development has seen the largest percentage cuts to its budget. In most local authorities, though, planning is a fairly small department so its share of the total cuts has been relatively small. Adult social care has provided most of the savings but because it accounted for a lot of spending in the first place, the percentage cut isn’t as great.

One of the first things to jump out of these charts is that, while everything else has been cut, spending on children’s social care has been increased. It’s not difficult to see why. A child’s death will bring forth tabloid outrage. The same newspapers that demand cuts and the sacking of useless council bureaucrats start shouting ‘something must be done’ and ‘never again’ as soon as a child is killed.

Many of the other services cut are those that many people don’t see or ones where the impact will not be seen for some time. Unless you have an elderly, disabled or vulnerable relative, you probably wouldn’t notice cuts to social care. Spending reductions in planning won’t come to light until someone (probably another austerity cheerleading tabloid) notices the proliferation of nightclubs and betting shops in a given area, or asks why so many houses have been built on a flood plain. Likewise, the effects of halving spending on traffic management and building control may not be seen for years.

What about efficiency savings, you might say. Well so far, local authorities seem to have done quite well. For example, environmental health inspections have fallen by 26 percent. Given that spending has fallen by 33 percent, that’s an efficiency saving.

It was a similar story in social care. The NAO notes:

- In the 2 years before 2010-11, local authorities saw little real-terms change in the total cost of these services. This was the net outcome of local authorities providing fewer services, which cost them more.

- This changed significantly in the 2 years after 2010-11, where local authorities saw large savings in these service areas. These savings resulted in local authorities providing fewer services, which also cost them less to provide.

- This pattern ended in 2013-14, with savings from these activities limited and delivered entirely through reductions in activity, rather than price.

More efficient public services aren’t necessarily better ones. Doing a bit less for a lot less makes a service more efficient, though it might not look that way to the service users.

But efficiency can only go so far, as the example above shows. Furthermore, the problem with big cuts to small departments is that you soon reach a point where if you cut them any more you might as well stop doing the activity altogether. For example, regulatory activities like building control and environmental health are only any use if there is a reasonable amount of enforcement. Chop them too much and you might as well not bother.

Even though most local authorities have done a good job in managing spending cuts, the NAO found that an increasing number of councils are having to make unplanned cuts or use of reserves part way through a financial year. As David Walker said last week, local authorities cannot go into deficit like NHS trusts. They have to balance their budgets. Unforseen expenses can leave them short. They then have no choice but to dip into reserves or, if they don’t have any, to save money by cutting something else.

Local authorities, say the NAO, expect things to get a lot more difficult after 2016. Local auditors doubt that councils have the capacity to maintain the pace of spending cuts achieved over the last four years. If the next government pushes ahead with the fiscal plans set out by the current one, the cuts will be much steeper in the next parliament. This is likely to cause severe problems for councils.

Many auditors referred to local authorities with substantial unfilled ‘funding gaps’ for 2015-16 and beyond. Auditors are generally positive about local authorities’ financial management and take confidence from their authorities’ track record in delivering savings. They are, however, clearly concerned that some authorities have been unable to identify ways of making anticipated savings for 2015-16 and beyond.

Where authorities have identified ways of making savings over the medium term, these often involve substantially redesigning and transforming services. These initiatives are required for local authorities to continue to make savings, but are also inherently risky. Auditors identified the long timescales required, the complications of setting up partnerships for activities such as shared services, the difficulties of introducing new job roles and ways of working, and uncertainty as to whether savings will materialise as planned and on schedule.

All of which suggests that, when it comes to savings, most the low hanging fruit in local government has been picked. Another £48 billion of cuts in the next parliament could finish some council services off.

Local authority cuts in the next parliament will have to come in the areas which affect a lot more people and some of them may come very suddenly. It would only take some unexpected expenditure, caused, for example, by something like last year’s floods, for some councils to run out of money. To balance the books they could then be forced to simply shut some services down.

At the Resolution Foundations Parliament of Pain event yesterday (of which more later), Giles Wilkes said that Conservative plans for the next five years would lead to “the absent-minded destruction of the state”. That is a succinct summary of the outlook for local government. After 2016, pressure on councils will become severe. As they start to run out of cash, the cuts are likely to be piecemeal, random and uneven. We will amble in a bemused daze towards the shrunken state of the future.

Update: A long interview with Newcastle City Council’s leader by John Harris and a shorter summary here.

By 2017-18, we will have less than £7m to spend on everything the city council does, above and beyond adult and children’s social care.

Thanks to Paul Anders for the link.

Squeezing adult social care increases the burden on health care. Through inability to support people in the community so they swing back and forth into bedded health facilities, and lack of adequate social care contributing to deterioration in health.

Reblogged this on Citizens, not serfs.

Reblogged this on sdbast.

“…the problem with big cuts to small departments is that you soon reach a point where if you cut them any more you might as well stop doing the activity altogether.”

That’s going to happen. It’s no surprise, just a case of when councils no longer provide libraries, museums and other “cultural” activities, along with a lot else besides.

Devolution has begun to swing the consensus towards taxation being controlled at a more local level. Perhaps we’ll see counties collecting and keeping taxes from their businesses and residents, passing a small stipend on to national government for defence, then managing their affairs from the revenues they have raised. The thought that they are compelled to balance the books will come as a relief to as yet unborn children, onto whom we are shamelessly loading the debt repayments for our current spending excesses.

This is an enticing prospect. It would allow democracy finally to flourish: if you want a high-tax, high-spend council, vote for it, get it, pay for it, enjoy the results. This might re-inject some sense that a vote counts, spur better candidates to run for council elections than the usual dullards that infect those institutions now, and allow more granularity and nuance in policy to recognise the differing viewpoints of the electorate across the country. Bring it on.

Unfortunately the USA stands as a good example as to what happens with such localisation. People vote to cut taxes, but rarely at all to raise them, meaning that services are cut left and right.

Whether we’d be able to educate enough people to realise the connection between taxes and services is unclear, especially with ukip types blaming all the spending on asylum seekers and civil servants.

Moreover, if you read the previous posts, it is clear that most of the population won’t have the money to be taxed anyway. This would permanently lock regional disparities in place and make death spirals even more likely.

I should have thought it was impossible for Whitehall to know ‘what is the right number of traffic wardens in Bolton’. We hear much of the evils of micro-management and most think such would be a bad thing. So what is the feedback mechanism? Votes and the control of local and county councils. This might beg the question – how might this electoral inconvenience be manipulated? PH’s ideas look attractive – but turkeys/Christmas.

Then there is the question how the underfunding works out, is there a danger councils will get rid of cheap young employees whilst keeping the expensive-to-pay-off old guard. After all, social workers on zero hour contracts sounds a smart idea to a shiny-shoe consultant.

Social unrest? Who cares, Thereas’s new legislation will see off troublemakers long before they get on coaches to London. The period 2015-2020 may see the real motivations come into play. What is troubling is the press down on those lower down the heap, risky but without leadership nothing much is likely to happen.

“Giles Wilkes said that Conservative plans for the next five years would lead to “the absent-minded destruction of the state”.”

Hmmm. Not sure it is absent minded. Osborne has in terms announced his intention to shrink the state. If LAs can no longer deliver services then that will be a success in Osborne’s eyes.

On the point about LAs not being permitted to go in deficit, are they not allowed to issue bonds, just as central government does, to fund a deficit?

The linked piece by John Harris also contains this interesting piece of information:

In Guildford in Surrey, for example, the cuts between 2010 and 2013 worked out at £19 per resident; in Newcastle, it was £162.

It would be more interesting to see those numbers as a % of central government funding and a % of public spending in those areas. I know that Surrey has for decades received one of the lowest central government settlements in the UK, so had far less low hanging fruit to pick.

Earlier this year I read an interview with a council leader in the North West of England who bemoaned the disappearance of regeneration money the LA had been using to top up its budgets for decades. The unstated subtext (which was no surprise to a former resident like myself) was that the LA had become reliant on the money not for genuine regeneration but as a slush for regular spending. It’s not a secret that for many years there was plenty of money sloshing around North West England through various agencies if you knew how to milk it and I suspect same is true of North East England. If you don’t believe this take a wander around Salford Quays or the Liverpool Waterfront.

These underlying factors skew the comparisons, if the LA never had much to start with smaller cuts in absolute terms can represent much larger cuts relatively. I wonder if the residents of Guildford ever got the £162 that the residents of Newcastle lost? Marginal constituencies in South East England are an interesting one to look at, compare how much central government funding they get per head versus true blue Surrey, it doesn’t stack up that Tory policy has been kind to Tory LAs. I think what is true is that some LAs have found frugality easier because they never had much anyway, whereas some have had a major culture shock as fairly easy access to money with relatively weak accountability has dried up in a short period of time.

Cutting planning, development, transport etc also has a long term impact on the investment/growth capacity of the area. For many councils, facing the extinction of grant in the next five years, the ability to thrive and grow is fundamental to becoming simply managers of rationed decline. So it remains important that those services can and do function effectively for long term fiscal and economic health. Councils also have a long-term responsibilities beyond reaction to the latest crisis.

The literature on fiscal federalism says that highly redistributive functions should be funded and organised at the highest possible level to avoid Tiebout effects (“voting with your feet” — the reason why shire counties and inner cities look different). LA finance is being undermined not just by cuts but by demographic risks which they cannot hedge. Why is no one suggesting, then, that social care stop being be a local function? The route to a solution should partly lie through a reconsideration of the cost base and the level at which functions are funded; the devolution debate has clouded discussions when things could move in both directions to better match local property tax bases with locally provided functions. U.S. states, for example, have discovered that funding education through municipal property taxes resulted in unequal outcomes, leading some states to centralise funding (with additional state regulation and oversight). Not a panacea but, as Herb Stein says, “something that cannot go on forever, will stop.”

“Furthermore, the problem with big cuts to small departments is that you soon reach a point where if you cut them any more you might as well stop doing the activity altogether.”

May I also say that big cuts to big departments has the same affect as witnessed by HMRC whose enforcement at local level is virtually non-existent.

Pingback: Saving Our Safety Net Fact of the Week: councils’ housing services cut by a third - ToUChstone blog